By Katrin Geist

By Katrin Geist

Guest Writer for Wake Up World

The one sentence summary of this article goes: I prefer butter from grass fed cows to margarine. If you would like to know what led to this conclusion, find out below.

Both butter and margarine serve the same purpose: they enhance flavor. We use them in baking, cooking, and as spreads. We’re so used to multiple options of both on supermarket shelves we hardly stop to think what we’re actually looking at, let alone how it’s made and what it contains.

For butter, that’s simple: the label on the one I just bought reads: “Cream, water, no added salt. Contains milk. Milk fat 80% minimum”. Butter has been a staple for millennia and is obtained from churning cream until hard. That’s it. You can make your own in under 5 minutes. Four cups of 35% cream yield c. 500g butter. Margarine, on the other hand, is a more recent 19th century invention using mostly plant oils, rather than animal fats. It is an engineered food. As such, it requires more processing steps to turn a liquid vegetable oil into a solid spread.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

Why and how did margarine come about in the first place?

It all started with a French emperor’s desire to feed the working class and the army. In an attempt to make butter more affordable by finding a suitable alternative, Louis Napoleon III offered a prize to the person presenting an adequate solution. Much to the dairy industry’s dismay, that person was French chemistHippolyte Mège-Mouriès. The year was 1869, and margarine was born as a butter substitute, at half its price. Mège-Mouriès’s margarine originated from beef fat, though, and plant oil based margarine was developed later, helped along by the influences (ingredient shortages) of the Great Depression and WW2. From 1950 onward, US margarine usually consisted of plant based fats (Clark 1986), which is what we see on supermarket shelves today.

Margarine resembles butter in many aspects: looks, texture, smell. It differs in ingredients and production process. Hydrogenation (adding hydrogen to unsaturated plant oils), invented in 1903, turns liquid plant oils into more solid spreads at room temperature by increasing their melting point. This treatment creates trans-fats (see below) and also decreases the vulnerability of oils to go rancid at room temperature under the influence of light, oxygen, and heat: product shelf life improves. The early food engineers were likely unaware of trans-fats and their impacts on biology. Their aim was to create a product to replace butter. However, as analysis technology further developed, evidence for the existence and negative impacts of trans-fats emerged and between 1960 – 1990 numerous studies appeared, with conflicting results (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). This changed in the 1990s, where the negative effects of partial hydrogenation and resulting trans-fats on serum cholesterol bore out consistently across multiple studies (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). After next to ignoring them for 50 years, the negative effects of trans-fats is well recognized today (Franklin Institute, Puligundla et al 2012).

What is fat? Why does the body need it? In what form?

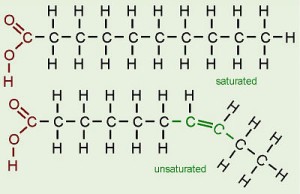

Fat (lipids), like sugar (carbohydrates) and protein (amino acids), is a fundamental building block of biology, consisting of a carbon chain saturated (or not) with hydrogen atoms and a COOH head, rendering the molecule a (fatty) acid (Fig 1). Fat yields twice as much energy compared to sugar, and mammals can convert sugar to fat, but not vice versa. We must derive essential fatty acids (omega 3 & 6) from our diet. Fats ensure proper brain function (your brain consists of 60% fat), help carry, absorb and store fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), provide fuel and energy storage, and are the fundamental cell membrane component, among many other functions. From essential fatty acids, the body can make its own more complex, longer chained fats (eg AA, arachidonic acid and DHA, docosahexaenoic acid, the most abundant brain fat) to incorporate into membranes. Some of these are also available as precursors from food directly.

Fatty acids form the key element of all biological membranes, composed of a thin fatty acid bi-layer (Fig 2). Membranes create compartments between and within cells (organelles, eg mitochondria, nucleus). Each of our c. 50 trillion cells uses a membrane which selectively admits some substances, but not others. Membranes are very important for life. They confer properties to cells and are characteristic of them. A cell’s membrane configuration allows it to participate in metabolic functions – or not. For instance, when a food particle reaches a cell that has no receptor for it, that cell is literally blind to what’s floating past in the blood stream and cannot use it. No receptor, no interaction. Cell membranes are dynamic and adaptable, not static. For example, cancerous cells increase their sugar receptors >20-fold compared to their healthy counterparts (see documentary Truly Heal from Cancer), which is why it’s vitally important to limit sugar consumption while experiencing cancer.

Cells communicate and interact through their unique membrane structure (Lipton 2004), the core part of which is – fat (Fig 2). So we need fats to maintain proper cellular function. They’re actually very important, and not to be condemned. Question is: are all fats equal?

Natural vs processed fats

Short answer: no. Longer answer: naturally saturated fats are solid at room temperature and do not turn rancid from cooking. Sources of saturated fats are mostly animals (red meat) and some plants (eg coconut), or derived products thereof (eg butter, cheese, ice cream, coconut & palm oils). Oleic acid is one of the most common (mono-unsaturated) fats in our diet (main component of olive, almond, pecan, macademia, peanut and avocado oils) and body. Ideally, we maintain a 1:1 balance of poly-unsaturated omega 3 and omega 6 fats. Often, Western diets do not reflect this ratio, but tend to be much higher in omega 6 fats (present in vegetable oils, nuts, poultry) – up to 20 times or more (Franklin Institute). Natural fats are those readily available without much processing.

Processed fats, on the other hand, are just that: subject to processing. Poly-unsaturated vegetable oil (eg corn, rapeseed, safflower, sunflower, grape seed) stays liquid when refrigerated, and is unstable at room temperature, prone to oxidation and rancidity. Vegetable oils produce trans-fatty acids when heated while cooking and deep-frying, and during the industrial process of hydrogenation (see Puligundla et al 2012 for details on hydrogenation). Examples of foods containing trans-fats: margarine, french fries, donuts, popcorn, commercially baked goods, potato chips, snack foods, sauces, crackers, mayo, salad dressings – anything that contains partially hydrogenated oils.

The production process of oil involves pesticides, solvents and metals which may remain in the final product (Puligundla et al 2012). Repeated heating during oil processing renders it rancid, the reason why deodorization is part of the process, before final packaging in some form of plastic with its own inherent problems. Additionally, a lot of vegetable oils come from genetically engineered plants (GMO, genetically modified organisms). Common ones are corn and rapeseed. “Canola” oil is a prominent brand. Margarine, baking shortening and frying fats may contain up to 40-50% trans-fats (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008).

Trans-fats

Trans-fats rarely occur in nature (Puligundla et al 2012). That said, ruminant animal’s milk contains between 1-8% natural trans-fats (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). However, contrary to industrially produced trans-fats, ruminant trans-fats are thought to be harmless when consumed in normal amounts (Willet & Mozaffarian 2008).

The chemical structure and shape of industrial trans-fats differs from natural fat, affecting physiological processes downstream where building blocks derived from trans-fats may not necessarily suit the intended purpose or change functional properties. It’s kind of like fitting a slightly off puzzle piece into a puzzle. It works, but is not quite right. If your puzzle contains too many malformed pieces, the overall result suffers, and the puzzle may change shape and fall apart, losing its function. In the rat model, French researchers found that trans-fats changed the electric conductivity of brain cells (which communicate through electric pulses). Further, they also reported a doubling of trans-fat incorporation into brain cell membranes when the diet was deficient in omega 3 ALA (alpha linolenic acid) (Franklin Institute). A change in molecular shape challenges highly specific (shape-dependent, as lock to key) enzymes that break down fats: they struggle to do so with a changed molecular configuration.

So trans-fats are like off puzzle pieces. Too many of them cause problems, and they’re best avoided altogether (Franklin Institute). They lead to more densely packed cell membranes, rendering them rigid and inflexible, thereby changing their properties (Franklin Institute). A meta-analysis of 140.000 participants showed a 23% increased incidence of coronary artery disease after increasing energy intake from trans-fats by 2% (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). Trans-fats negatively influence blood cholesterol levels (Zock & Katan 1997) and can activate a systemic inflammation response (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). They cause or exacerbate cancer, atherosclerosis, heart disease, auto-immune disease, tendon and bone degeneration, type 2 diabetes, endothelial dysfunction, problems with fertility and growth, osteoporosis, allergic sensitization in 2 year olds, eczema, among others, and are present in mother’s milk (Sausenthaler et al 2006, Mente et al 2009, Weston A. Price Foundation 2009, Dalainas & Ioannou 2008, Franklin Institute).

Our body must use the building blocks we feed it. The consumption of trans-fats provides no apparent benefit, but, as seen, considerable potential for harm (DiNicolantonio 2014). Denmark enacted respective legislation in 2003, virtually eliminating industrially produced trans-fats (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008). They pose an unprecedented challenge to our body in its 1000s of generations of evolution. Yet, foods rich in trans-fats remain abundant in our food supply. The obvious remedy is to stay away from products containing them. Reading labels and becoming a “fringe shopper” in supermarkets are certainly excellent choices. Health care starts at home (and in the supermarket). Use your power of discernment!

The rise of margarine

During WW2, margarine was a uniform product in two versions (cheap and more expensive) manufactured by one company and distributed under government allocation orders. For example, in the 1940s, each person was eligible to 8oz of fat per week. Two of those had to be margarine, the rest could be either butter or margarine (Clark 1986). Food adulteration has long been a problem, and entire departments were created to ensure that butter was butter and margarine remained margarine, as declared on the packaging (Deelstra et al 2014), difficult times or not. Pre- WW1 and WW2 margarine was mostly distributed in bulk, and people would buy it at the shop by unit of weight. Post WW2, government rules eased. Individual packaging came along. And with it, influencing consumers with brands (logos, colors, text). Shops shifted from offering bulk to individually packaged products. Easing of regulations gave rise to competition, aggressive brand marketing and advertising (at first largely unregulated), following the economics of supply and demand (Fig 3)(Clark 1986).

While there was hardly any margarine advertising prior to 1900, in 1954 the advertising budget of one Dutch margarine brand was 500.000 British Pounds. Reaching out and influencing buyers through the media was well and truly under way. TV advertising (of this brand) began in 1955. That year, margarine production surpassed that of butter, continuing its success from during and immediately after the war (Clark 1986).

Why did butter get such a bad reputation?

The earliest records of butter go back as far as 3500 BC. In all the time since then, nobody ever thought it problematic – until the 1950s, where a new trend emerged: while margarine was first marketed as the butter substitute that it was, with a goal to resemble butter as much as possible, new research at the time suggested that saturated fats and cholesterol – as found in butter and other animal fats – were unhealthy and linked to heart disease (Keys 1953 & 1970 in Ravnskov 1998).

With heart disease on the rise in the US at a puzzling rate – a 500.000 fold increase between 1921 and 1960 (Fallon-Morell 2009) – people welcomed to finally know the underlying cause. Contemporary research also reported possible benefits of poly-unsaturated fats (Weston A. Price Foundation). These results flowed into what’s still known today as the “Diet-Heart” or “Lipid Hypothesis”: that saturated animal fats raise blood cholesterol which then causes heart disease by hardening and clogging up arteries (atherosclerosis), resulting in a possible heart attack. This hypothesis was highly influential (Ravnskov 2002) and led the American Heart Association to inform people that consuming animal fats causes coronary heart disease. For a healthy heart, therefore, one should prefer unsaturated fats – the basis of margarine. The US government followed up by recommending a diet higher in carbohydrates and lower in fat to prevent heart disease (Hite et al 2010).

Thus, butter turned a “bad fat” for decades to come and margarine was established (and marketed) as the healthy alternative due to its lower saturated fat content (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008) and richness in poly-unsaturated fats. In public perception, margarine turned into a health food. The use of partially hydrogenated fats accelerated in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s as food producers responded to public health organizations to move away from animal fats (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008).

There was only one problem: one of the central studies purporting the “Lipid Hypothesis” was majorly flawed (Ravnskov 1998, DiNicolantonio 2014). Data were omitted and misrepresented. When re-analyzed, trends turned out a lot weaker (Ravnskov 1998). The result: there’s little to no evidence that a high fat diet causes heart disease (Ravnskov 1998, “Fat Head” 2009, Mente et al 2009, Hite et al 2010, Diamond 2011, Lundell 2012), and data in support of a low fat diet are lacking (DiNicolantonio 2014). Despite scarce valid evidence for the above cholesterol story we all know and lots against it and the connection between saturated fat intake and coronary heart disease (Weston A. Price Foundation 2000, Siri-Tarina et al 2010, Ramsden et al 2013), the (misinformed) public still thinks of the low-fat diet tale as well established, almost doubtless scientific fact. How did we get here?

The influence of published opinion on consumers: cholesterol & saturated fats

Just to what degree does marketing influence our lives? I think it’s much more than we are aware or like to admit (Moynihan & Cassels 2005, Taylor 2009).

It’s amazing how select published opinion, be it as technical paper, magazine article, institutional declaration, government recommendation or marketing campaign, takes root and drives perception. Sometimes for generations. The use of partly hydrogenated oils increased on the back of the low fat craze, catering to an increased demand of unsaturated, low fat products based on the questionable premise that cholesterol and animal fats cause heart disease and should be avoided. Favorable published opinion sells product and old myths die hard. I remember the low fat hype growing up in 1980s Germany.

As early as 1936 it emerged there was no correlation between cholesterol levels and atherosclerosis, as published by Landé & Sperry (in Fallon-Morell 2009) and Gertler et al (1950). A later dietary study in 1965 found patients after a heart attack had highest survival rates when consuming animal fat (75%), as opposed to olive oil (57%) and corn oil (52%) (Fallon-Morell 2009). Interestingly, the “Lipid Hypothesis” took root regardless.

Recent literature provides clear evidence that the global epidemic of atherosclerosis, heart disease, diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome is driven by a diet high in carbohydrates (sugar, flour, bread, potatoes), rather than fat (DiNicolantonio 2014). That one could lose weight by reducing carbohydrates was already known and successfully practiced in 1864 (Diamond 2011). Replacing saturated fats with carbohydrates or poly-unsaturated fats (namely omega 6s) in our diet is potentially harmful (Ramsden et al 2013, DiNicolantonio2014). An excess of omega 6 fats causes inflammation (Lundell 2012).

A meta-analysis of 21 studies looking into the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and coronary artery disease as a result of dietary saturated fats concluded there was no association between consumption of saturated fats and increased risk for these conditions (Siri-Tarino et al 2010), a result echoed by Chowdhury et al (2014) who analyzed 72 studies and found no support of “current cardiovascular guidelines that encourage high consumption of poly-unsaturated fatty acids and low consumption of saturated fats”.

And to ease the blame on butter further: its use decreased between the 1920s and 1990s, while coronary heart disease and cancer increased (Fallon-Morell 2009). Changes in trans-fatty acid intake roughly correspond with the epidemic of coronary artery disease (Dalainas & Ioannou 2008, Puligundla et al 2012), and Felton at al (1994) concluded that omega 3 & 6 fats form a significant part of human aortic plaques, suggesting that “the protective effect of increased intake of poly-unsaturated acids may have been overstated.” This is seconded by Ravnskov (1998), who concludes that “There is little evidence that saturated fatty acids […] are harmful and that poly-unsaturated fatty acids […] are beneficial”. But there is evidence that margarine intake increases risk of coronary heart disease and butter does not (Gillman et al 1997).

Cholesterol is a vital molecule for good health, and one that our body produces on its own. It’s a large sterol (not a fat) important for cell membrane structure (Fig 1), wound repair, the nervous system, as an antioxidant, and as precursor of vitamin D, bile salts, and sex hormones (Fallon-Morell 2009). There’s no need to demonize it. It has been known for a long time that dietary cholesterol hardly influences blood serum cholesterol levels (Gertler et al 1950, Ravnskov 2000). Former heart surgeon Dr. Dwight Lundell shares this view. I highly recommend to read what he says or listening to this interview touching on the ways in which industry compromises well meaning doctors and researchers – and ultimately, government agencies (Fallon-Morell 2009).

Regarding the latter, the latest development of great concern is TPP (Trans Pacific Partnership). This “partnership” prunes protective consumer laws, some of them centuries old (Deelstra et al 2014), to accommodate industry – the center of its interest, rather than people’s wellbeing. And relating to heart disease and the workings of questionable facts turned public health recommendation, watch what neuroscientist Dr. David Diamond shares in his 2011 talk “How bad science and big business created the obesity epidemic” or read this critical account of the flawed foundations of US national dietary guidelines (Hite et al 2010).

The film “Fat Head” (2009) by comedian and former health writer Tom Naughton offers a humorously different perspective on fat and what fuels published opinion. It is an interesting and entertaining must watch that challenges what we thought we knew about fat and “healthy eating”. Did you know one could lose weight by only eating fast food for a month…? Not that I advocate this kind of diet. But it illustrates the film’s point. Sorry to spoil the plot. It’s still worth watching though!

Some even say that higher cholesterol in women of all ages and people over 60 is associated with a longer life span (Fallon-Morell 2009, Ravnskov 2002). Apparently, a cholesterol level below 160 is a predictor of depression, cancer, violent behavior, stroke and suicide, and lower cholesterol was associated with greater risk of death (Fallon-Morell 2009) – the puzzling conclusion from this flies in the face of commonly held belief:higher cholesterol may be better for us than lower cholesterol (Ravnskov 2003). Nutritional guidelines have been confusing people for a long time (Steel 2005, Hite et al 2010).

Maybe we should take a hint from our own bodies: nearly every cell – almost all ~ 50 trillion of them – can produce cholesterol. That’s how important it is. Interestingly, William Castelli, director of the famous Framingham study, often cited in support of the “Lipid Hypothesis”, said this about its results, in a different publication: “The more saturated fat one ate, the more calories one ate, the lower the person’s serum cholesterol. […] The opposite of what the equations provided by Hegsted et al and Keys at al would predict. […] The people who ate the most cholesterol, ate the most saturated fat, ate the most calories, weighed the least, and were the most physically active”(Castelli 1992).

So what to make of all of this?

Butter vs margarine

Milk fat contains about 400 different fatty acids, most of them saturated (70%). Unsaturated fats make up approximately 25%, and naturally occurring trans-fatty acids in milk comprise c. 2%. Butter is about 80% fat, the rest mostly water. Other components include cholesterol, minerals, vitamins and phospholipids. For a longer list of butter constituents, see this article.

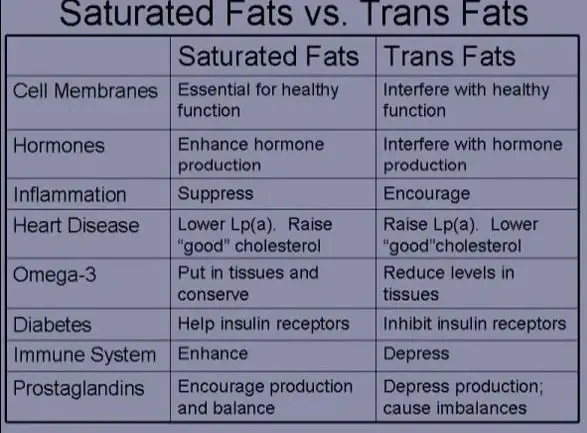

As mentioned at the beginning, fats serve important physiological functions: saturated fats make up ~ 50% of cell membranes, are important for bone calcium, heart, liver & kidney function, and support the immune system & detox mechanisms (Fallon-Morell 2009). Trans-fats on the other hand, influence the body negatively and are best avoided. Fig 4 contrasts some physiological effects of natural saturated fats vs industrial trans-fats.

Margarine manufacturing guidelines vary between countries, but generally margarine contains 80% fat, oils from animal or vegetable sources, and vitamins A & D. The aqueous content may be milk, water, or a soy-based protein liquid. Like milk it must be pasteurized and may also contain a salt substitute, sweeteners, fatty emulsifiers, preservatives, and coloring agents. Not to mention trans-fats and involuntary ingredients such as pesticides, solvents, and metal. Repeated heating during manufacture also turns vegetable oils rancid.

Recognizing the danger and negative image of trans-fats, an increasing proportion of margarines do not contain them anymore, so – as always – it pays to read the label. Palm oil and coconut oil, for example, do not require hydrogenation as they are naturally semi solid. Yet, palm oil is problematic for the way it’s sourced (tropical deforestation to establish plantations) (Isenhour 2014). When in doubt, coconut oil based products may be the better choice.

And even if margarine does not contain trans-fats, in my mind, it’s still a highly processed food.

In closing….

When I set out to write this piece, I had no intention to delve in so deeply. I simply thought to investigate what’s better, butter or margarine. Little did I suspect this was such a huge story, present in so many layers and aspects – perhaps I’ve been living under a rock for the past decades. At any rate, I certainly learned a lot researching this topic. It’s a bit unsettling what comes up when you begin looking and question things you thought were harmless or just took for granted – such as the all too commonly known “fact” that animal fat and cholesterol cause heart disease. I guess the biggest lesson is to take nothing for granted. As the saying goes: “Assume nothing. Question everything”. Select your truth provider wisely. =)

Considering all of the above, needless to say, I don’t bother with margarine. Why use a highly processed product when the original (butter) is readily available and easily made at home? Simple is best. I also find it important to consider just how much “knowledge” about the benefits (or detriments) of something comes from marketing efforts and not primary sources such as research papers. And even those can be bought or omitted in official reports (Moynihan & Cassels 2005, Hite et al 2010). Getting to the root of things is work and can be tricky, especially with complex subjects such as this, including many data, opinions, and stakeholders (Steel 2005).

Bottom line: own investigation is best. I shared my current results here and hope you find them useful. Doubt any or all of it? Excellent! I invite you to start reading and find out for yourself. Enjoy the ride.

I’m off now for some freshly homemade bread with butter and (real) salt sprinkled on top!

For more articles like this, sign up to my monthly Healthy Living Newsletter and receive a free report on the Scientific Basis of Energy Healing, or like us on Facebook!

Article References

- Castelli WP. 1992. Concerning the possibilities of a nut…. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152(7):1371-1372.

- Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, et al. 2014. Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids With Coronary Risk. Review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:398-406.

- Clark P. 1986. The Marketing of Margarine. European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 20 Iss 5 pp. 52 -65.

- Dalainas Iand HP Ioannou. 2008. The role of trans fatty acids in atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease and infant development. International Angiology; Apr 2008; 27, 2; ProQuest Central pg. 146

- Deelstra H, Thorburn Burns D and MJ Walker. 2014. The adulteration of food, lessons from the past, with reference to butter, margarine and fraud. Eur Food Res Technol (2014) 239:725–744

- Diamond D. 2001. Presentation at USF titled: “Myths and misinformation about saturated fat and cholesterol: how bad science and big business created the obesity epidemic.” watch video or download powerpoint pdf.

- DiNicolantonio JJ. 2014. The cardiometabolic consequences of replacing saturated fats with carbohydrates or?-6 polyunsaturated fats: Do the dietary guidelines have it wrong? Open Heart 2014;1:e000032.

- Fallon-Morell S. 2009. “The Oiling of America” presentation.

- Felton CV, Crook M, Davies MJ and MF Oliver. 1994. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and composition of human aortic plaques. Lancet 1994, 344:1195-96.

- Hite AH, Feinman RD, Guzman GE, Satin M, Schoenfeld PA and RJ Wood. 2010. In the face of contradictory evidence: Report of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee. Nutrition 26 (2010) 915-924.

- Isenhour C. 2014. Trading Fat for Forests: On Palm Oil, Tropical Forest Conservation, and Rational Consumption. Conservation and Society 12(3): 257-267, 2014.

- Gertler MM, Garn SM and PD White. 1950. Diet, serum cholesterol and coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1950;2:696-704.

- Gillman MW, Adrienne Cupples L, Gagnon D, Millen BE, Curtis Ellison R and WP Castelli. 1997. Margarine intake and subsequent coronary heart disease in men. Epidemiology Vol 8(2): 144-149.

- Hite AH, Feinman RD, Guzman GE, et al 2010. In the face of contradictory evidence: Report of the Dietary Guidelines for Americancs Committee. Nutrition 26 (2010) 915-924.

- Keys A. 1953. Atherosclerosis: A problem in newer public health. Am J Epidemiol 1976; 104:J Mount Sinai Hosp NY 1953; 20: 118–139.

- Keys A. 1970. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. Circulation 1970; 41(Suppl. 1): 1–211.

- Lipton B. 2004. The Biology of Belief. Hay House Inc.

- Lundell D. 2012. (Heart Surgeon blog article & interview)

- article: myscienceacademy.org/2012/08/19/world-renown-heart-surgeon-speaks-out- on-what-really-causes-heart-disease

- interview: youtube.com/watch?v=E5jgrB2RblY

- Mente A, de Konig L, Shannon HS and SS Anand. 2009. A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Causal Link Between Dietary Factors and Coronary Heart Disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):659-669.

- Moynihan R and A Cassels. 2005. Selling sickness: How the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies are turning us all into patients. ISBN-13: 978-1560258568.

- Puligundla P, Variyar PS, Ko S and VSR Obulam. 2012. Emerging Trends in Modification of Dietary Oils and Fats, and Health Implications – A Review. Sains Malaysiana 41(7)(2012): 871–877.

- Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, et al. 2013. Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis. BMJ 2013; 346:e8707.

- Ravnskov U. 1998. The Questionable Role of Saturated and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, June 1998. Pages 443–460.

- Ravnskov U. 2000. “The cholesterol myths. Exposing the fallacy that saturated fat and cholesterol cause heart disease.” (free ebook)

- Ravnskov U. 2002. A hypothesis out-of-date: The diet–heart idea. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 55 (2002) 1057–1063.

- Ravnskov U. 2003. High cholesterol may protect against infections and atherosclerosis. Q J Med 2003;96:927–934.

- Sausenthaler S, Kompauer I, Borte M, et al. 2006. Margarine and butter consumption, eczema and allergic sensitization in children. The LISA birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2006: 17: 85–93.

- Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB and RM Krauss. 2010. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:535–46.

- Steel F. 2005. A Source of Our Wealth, Yet Adverse to Our Health? Butter and the Diet–Heart Link in New Zealand to c.1990. Social History of Medicine Vol. 18 No. 3.

- Taylor E. 2009. Mind Programming. 338 pages. Hay House ISBN 978-1-4019-2331-0.

- The Franklin Institue

- Truly Heal From Cancer Article & Documentary

- Weston A. Price Foundation. 2000. The Oiling of America article.

- Willet W and D Mozaffarian. 2008. Ruminant or industrial sources of trans fatty acids: public health issue or food label skirmish? Am J Clin Nutr March 2008 vol. 87 no. 3.

- Zock PL and MB Katan. 1997. Butter, margarine and serum lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis 131 (1997) 7–16.

Further links:

- Elkaim Y. 2013. Super Nutrition Academy ~ Butter vs Margarine podcast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gzghqVEEqng

- The history of butter and margarine and their production:

- http://www.madehow.com/Volume-2/Butter-and-Margarine.html

- Dr. Dwight Lundell (Heart Surgeon)

- article: http://myscienceacademy.org/2012/08/19/world-renown-heart-surgeon-speaks-out- on-what-really-causes-heart-disease/

- interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5jgrB2RblY

- Canola oil: “The Great Con-ola” article, Weston A. Price Foundation 2002.

- Weston A. Price Foundation. 2001. What causes heart disease?

- Authority Nutrition: 7 reasons why butter is good for you.

- TEDMED: Dr.s Dean Ornish & Deepak Chopra

- TEDMED: Dr Peter Attia: What if blaming the obese is blaming the victims?

Previous articles by Katrin Geist:

- The Power of Convictions and How They Shape Our Lives

- 10 Significant Reasons Why Regularly Drinking Green Tea Is An Awesome Healthy Living Habit!

- Cradle to Cradle Design – How a Biochemist and an Architect Are Changing the World

- Truly Healing From Cancer and Preventing It Altogether

- How to Lose Your Mind and Create a New One

- Research Shows Promising Effects Treating Advanced Cancer with Light Frequencies

- Depression & Anxiety: Discover 3 Powerful, Drug-Free Ways that Help Thousands, Naturally

- The Power of Suggestion – Are You Asking the Right Questions?

About the author:

Katrin Geist, BA, MSc, combines her interests in consciousness, personal transformation, and natural healthcare as Reconnective Healing practitioner, speaker, and author. Her monthly “Healthy Living Newsletter” offers original articles like this one on relevant natural healthcare topics.

Katrin has held international Reconnective Healing clinics in several countries and currently works from her New Zealand office in Dunedin. To contact her for personal or remote sessions, send an email to [email protected], or call 0064 (0)21 026 95 806 NZ mobile).

Katrin’s website and blog at HolisticHealthGlobal.co.nz also offer more information on Reconnective Healing and how it helps people regain and retain their wellbeing – naturally and effortlessly: no pills, no needles, no side-effects. Trying this process may well be the best thing you ever did! No more than 3 sessions required to find out what difference this may make for you.

- Website: HolisticHealthGlobal.co.nz

- Facebook: Holistic Health Global Ltd

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 0064 (0)21 026 95 806 (NZ mobile)

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]