By Leo Hickman – guardian.co.uk

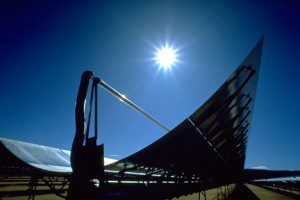

During the summer of 1913, in a field just south of Cairo on the eastern bank of the Nile, an American engineer called Frank Shuman stood before a gathering of Egypt’s colonial elite, including the British consul-general Lord Kitchener, and switched on his new invention. Gallons of water soon spilled from a pump, saturating the soil by his feet. Behind him stood row upon row of curved mirrors held aloft on metal cradles, each directed towards the fierce sun overhead. As the sun’s rays hit the mirrors, they were reflected towards a thin glass pipe containing water. The now super-heated water turned to steam, resulting in enough pressure to drive the pumps used to irrigate the surrounding fields where Egypt’s lucrative cotton crop was grown. It was an invention, claimed Shuman, which could help Egypt become far less reliant on the coal being imported at great expense from Britain’s mines.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

“The human race must finally utilise direct sun power or revert to barbarism,” wrote Shuman in a letter to Scientific American magazine the following year. But the outbreak of the first world war just a few months later abruptly ended his dream and his solar troughs were soon broken up for scrap, with the metal being used for the war effort. Barbarism, it seemed, had prevailed.

Almost a century later, a convoy of air-conditioned coaches sweeps through the affluent suburb of Maadi – where Shuman had demonstrated his fledgling solar panels – continuing south for 90km towards Kuraymat, an area of flat, uninhabited desert near the city of Beni Suef. The high-level international delegation of CEOs, politicians, financiers and scientists has come to visit a brand new “hybrid” power station that uses both natural gas and solar panels to generate electricity. Before the coaches reach the facility’s security gates, its 6,000 parabolic troughs – each six metres tall with a combined surface area of 130,000sq metres – are already visible from the perimeter road. Even though the panels account for just one seventh of the power plant’s 150MW generating capacity, the Egyptian government, which has been pushing to develop the site since 1997, hopes to prove to the delegation that it is the desert sun – not fossil fuels, such as gas, coal and oil – that should be used not only to generate far more of the electricity across the Middle East and North Africa (Mena), but, crucially, for neighbouring Europe, too.

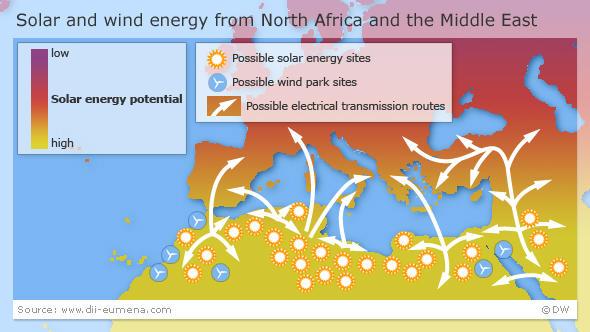

Gerhard Knies, a German particle physicist, was the first person to estimate how much solar energy was required to meet humanity’s demand for electricity. In 1986, in direct response to the Chernobyl nuclear accident, he scribbled down some figures and arrived at the following remarkable conclusion: in just six hours, the world’s deserts receive more energy from the sun than humans consume in a year. If even a tiny fraction of this energy could be harnessed – an area of Saharan desert the size of Wales could, in theory, power the whole of Europe – Knies believed we could move beyond dirty and dangerous fuels for ever. Echoing Schuman’s own frustrations, Knies later asked whether “we are really, as a species, so stupid” not to make better use of this resource. Over the next two decades, he worked – often alone – to drive this idea into public consciousness.

The culmination of his efforts is “Desertec”, a largely German-led initiative that aims to provide 15% of Europe’s electricity by 2050 through a vast network of solar and wind farms stretching right across the Mena region and connecting to continental Europe via special high voltage, direct current transmission cables, which lose only around 3% of the electricity they carry per 1,000km. The tentative total cost of building the project has been estimated at €400bn ( £342bn).

Until now, Desertec has been seen by many observers as little more than a mirage in the sand; the fanciful plan of well-meaning dreamers. After all, the technical, political, security and financial hurdles can, each on their own, appear to be utterly insurmountable. But over the past two years, the initiative has received significant support from some of the biggest corporate names in Germany, a country that already leads Europe when it comes to adopting and developing renewable energy, particularly solar. In the autumn of 2009, an “international” consortium of companies formed the Desertec Industrial Initiative (Dii) with weighty companies, such as E.ON, Munich Re, Siemens and Deutsche Bank, all signing up as “shareholders”. Germany’s announcement earlier this year that, in the wake of the Fukushima disaster, it was to speed up its total phase-out of nuclear power suddenly pulled the Desertec idea into much sharper focus. Coupled with faltering international negotiations and increasingly dire warnings on climate change – just last month the International Energy Agency warned that the world is headed for irreversible climate change if it doesn’t start reducing carbon emissions within five years – it would seem the time is now right for an idea of such scale and ambition.

[youtube zjnqXEWGUAk 640 380]

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110317″]

Last month, at its annual conference in Cairo, Dii confirmed to the world that the first phase of the Desertec plan is set to begin in Morocco next year with the construction of a 500MW solar farm near to the desert city of Ouarzazate. The 12sq km project would act as a “reference project” that, much like Egypt’s own project at Kuraymat, would help convince both investors and politicians that similar farms could be repeated across the Mena region in the coming years and decades.

“It’s all systems go in Morocco,” announced Paul van Son, Dii’s CEO, to the visiting delegates. Talks, he added, were – given their shared close proximity, along with Morocco, to western Europe’s grid – already under way with Tunisia and Algeria about joining the “first phase” of Desertec. Countries such as Egypt, Syria, Libya and Saudi Arabia would be expected to join in the “scale-up” phase from 2020 onwards, once extra transmission cables were laid across the Mediterranean and via Turkey, with the whole venture becoming financially self-sustaining by 2035.

Van Son swats away any talk that the Desertec project is built on a precarious foundation of presumption, naivety and hope. “Yes, the current global financial crisis has clearly not been very helpful, but everyone also realises that being dependent on fossil fuels creates vulnerability,” he says.

To continue reading this story, please click here

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]