One of my former neighbours in my home town of Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, was a widow whose son was a sailor in the merchant navy.

He did not like to tell his mother when he would be coming home on leave because he was afraid she would worry if he was delayed on the way. But his mother always knew anyway — thanks to the family cat.

This pet was very attached to this young man and, an hour or two before he arrived, it sat on the front door mat and began miaowing loudly as if equipped with some sixth sense which told it that he was on the way.

The cat was never wrong and this early-warning system gave our neighbour time to get her son’s room ready and prepare him a meal in the certainty that he would turn up soon afterwards.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

This is just one of many examples of animals displaying the apparently psychic tendencies more normally associated with some of their human counterparts.

Many cats seem to know, for example, when they are going to the vet’s — hiding away in the hope that their owners might get bored of looking for them and give up on the idea.

More dramatically, some animals seem to sense when their owners have had accidents or have died in distant places — as documented on my database of more than 5,000 case histories involving psychic phenomena in animals.

This includes 177 cases of dogs apparently responding to the death or suffering of their absent masters or mistresses, mostly by howling, whining or whimpering, and 62 accounts of cats showing similar signs of distress.

Conversely, in 32 instances people knew when their pet had died or was in dire need, even when they were many miles away at the time.

As we will see, these paranormal powers are of potentially huge value to human beings in the prediction of natural disasters, such as earthquakes and tsunamis.

And yet, as someone who has spent his entire adult life working as a biologist, holding senior academic posts both here (UK) and in the U.S., I am constantly surprised and frustrated by the refusal of my colleagues in the scientific world to take them seriously.

Without acknowledging such phenomena, it’s difficult to see how we can fully understand the behaviour of not just cats and dogs, but wild animals such as wolves.

The latter were studied by naturalist William Long who, in 1919, wrote a book that described the behaviour of a pack he had followed in Canada. He found separated members of wolf packs remained in contact with each other and responded to each other’s activities while many miles apart.

On one occasion, a limping female became separated from the pack Long was tracking and lay recovering in a den while the rest of the wolves moved on. Days passed, then suddenly the female reappeared among the pack.

The wolves’ responsiveness appeared to involve far more than simply following habitual paths, tracking scent trails, or hearing howling or other sounds, and Long wondered whether the same abilities might be found in pets.

He described some simple experiments with a friend’s dog which showed a knack for predicting its master’s return home. The dog would go to stand at the door soon after its owner had started his journey from work.

No one followed Long’s lead in researching this because, among scientists, the subject of telepathy has always been taboo. But in the Nineties I began asking friends and neighbours if they had ever noticed that their animals could anticipate when someone was coming home. I soon received dozens of reports, and by 2011 my database included more than 1,000 accounts of dogs and more than 600 of cats behaving in this way.

In telephone surveys in Britain and the U.S., I found that in about 50% of dog-owning households and about 30% of those with cats, the animals were said to anticipate the arrival of a member of the family. And it was not just dogs and cats that were involved. More than 20 other species showed similar behaviour, especially parrots and horses, but also a ferret, several bottle-fed lambs raised as pets, and pet geese.

Many of those I spoke to made it clear that the animals’ responses were not simply reactions to the sounds of familiar cars or footsteps in the street. They happened too long in advance of the person’s arrival, and often even when they came home by bus or train. It wasn’t just routine. Some people were plumbers, lawyers and taxi drivers who worked irregular hours, but still their pets were ready to welcome them when they got home.

Intrigued by this, I carried out experiments. The most extensive were with a terrier called Jaytee, who lived near Manchester with his owner Pam Smart. Initial observations showed that he was at the window on 85% of the occasions when Pam returned home.

I wanted to be sure that this was not down to Jaytee learning Pam’s routine, or picking up on other clues, so in a series of more formal tests, we arranged for Pam to be at least five miles away from home during each test.

I then set up a camera to film Jaytee’s behaviour and each day selected a random time for Pam to return home, asking her to travel by taxi so as to avoid any cues which might have come from the engine noise of a familiar car. She did not know in advance when she would go home, but was informed when to do so by a pager.

On average, Jaytee was at the window only 4% of the time during the main period of Pam’s absence, and 55% of the time when she was on the way back.

I did similar experiments with other dogs, including a Rhodesian Ridgeback from Manchester called Kane.

He looked out of the window, with his paws on a front table, when his owner came home — but whereas Jaytee’s vigil began shortly before his owner set off, Kane took up his post only when his mistress was already homeward bound. Both these and the many other cases I have investigated suggest that these animals have some kind of telepathic bond with their owners.

Alongside telepathy, animals also seem to have a sense of impending doom. Since classical times, people have reported unusual animal behaviour before earthquakes, and I have collected much modern evidence.

In all these cases there were descriptions of wild and domesticated animals acting in fearful, anxious or unusual ways. Some possible explanations are that they pick up vibrations in the earth’s surface, or detect subterranean gases.

Or perhaps, as I am suggesting, animals rely on something which defies current scientific understanding. In the case of the Asian tsunami on December 26, 2004, they appeared to be aware that something was happening half an hour beforehand.

According to villagers in Bang Koey, Thailand, a herd of buffalo were grazing by the beach when they suddenly lifted their heads and looked out to sea, ears standing upright. They turned and stampeded up the hill, followed by bewildered villagers, whose lives were thereby saved.

Some animals anticipate other kinds of natural disaster such as avalanches, and even man-made catastrophes. During World War II, many families relied on their pets’ behaviour to warn them of air raids before official warnings were given.

The animal reactions occurred when enemy planes were still hundreds of miles away, long before the animals could have heard them coming, and some dogs in London anticipated the explosion of German V-2 rockets, even though these missiles were supersonic and could not have been heard in advance.

With very few exceptions, the ability of animals to anticipate disasters has been ignored by Western scientists, but things are very different elsewhere.

Since the Seventies, in earthquake-prone areas of China, the authorities have encouraged people to report unusual animal behaviour. In several cases they have issued warnings that enabled cities to be evacuated hours before earthquakes struck, saving tens of thousands of lives.

By paying attention to unusual animal behaviour, earthquake and tsunami warning systems might be feasible in parts of the world that are at risk from these disasters. Millions of people could be asked to take part in this project.

They could be told what kinds of behaviour animals might show if a disaster were imminent. If people noticed such behaviour, they would telephone a hotline. A computer system would analyse the places of origin of the messages. If there was an unusually large number, it would signal an alarm, and display on a map the places from which the calls were coming.

Exploring the potential for animal-based warning systems would cost relatively little. If it turns out that they are indeed reacting to subtle, physical changes, then seismologists should be able to use instruments to detect these and to make better predictions themselves.

If, on the other hand, it turns out that what we call ‘presentiment’ plays a part, we should embrace it, regardless of whether or not we understand it. Ignoring it, or trying to explain it away, will leave us less protected against the unexpected ravages of nature.

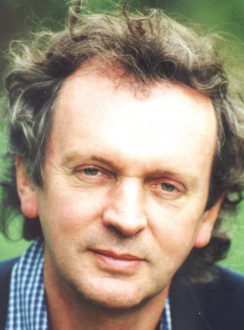

About the author:

Rupert Sheldrake, one of the world’s most innovative biologists and writers, is best known for his theory of morphic fields and morphic resonance, which leads to a vision of a living, developing universe with its own inherent memory. He is the author of The Science Delusion, published in January 2012 in the UK, where it is a bestseller, and due to be published in the US in September under the title Science Set Free. He worked in developmental biology at Cambridge University, where he was a Fellow of Clare College. He was then Principal Plant Physiologist at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), in Hyderabad, India. From 2005 to 2010 he was Director of the Perrott-Warrick project. , funded from Trinity College, Cambridge. (Read Dr. Rupert Sheldrake’s full biography here.)

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]