Guest Writer for Wake Up World

Far from being a competitive market, the same few big players dominate Australia’s corporate landscape.

If you go and ask the “average” Australian on a Melbourne or Sydney street who owns the banks and large public companies in Australia, most will answer “Australians through superannuation and mutual funds”. This belief gives Australians a sense of pride in “Australian private enterprise”, and may even assist Australians grudgingly accept high bank charges and interest rates: “after all, we own the banks”.

However, if one examines the annual reports of most of the large Australian public companies, names like HSBC, JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, and BNP Paribas are very prominent in the tops 20 shareholders lists. There has been a major shift in the Australian corporate ownership-scape over the last decade. And a silent one at that.

Let’s go back to the 1980s when Bob Hawke was Prime Minister of Australia. The ex-ACTU head did more than any other prime minister to liberalise the Australian economy. Hawke began deregulating the financial system, dismantled the tariff system, floated the Australian dollar, and privatised the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (planned under Hawke, executed under Keating). What was important here, there was no longer any distinction between savings and commercial banks, and foreign banks could apply for licenses to operate directly in the Australian retail market. Paul Keating followed on this liberalization path with the catch cry of creating a “level playing field”.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

These liberalizations allowed foreign investors to come into the Australian market, however foreign banks found it extremely difficult to start-up from scratch and compete with the local banks. However with the Asian financial crisis of 1997, and subsequent economic downturns within the Australian economy, foreign equity started slowly trickling in and buying up Australia’s prime corporate assets. Mutual and investment funds were specifically important as these made excellent vehicles for investment in corporate Australia.

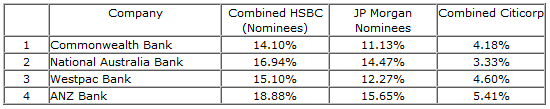

Today the ownership-scape of Australian banks is very different from the traditional past, where Australian banks were owned by the “average Australian” through superannuation and investment funds. Although major shareholders are in fact mutual and investment funds, they are now managed by foreign interests who appoint their “proxy” directors to the boards, as the table shows.

Table 1. Major Shareholders in Australia’s “Big Four” banks:

Apart from the top four shareholders shown above, an inspection of the data in the respective annual reports shows that most of the other top 20 shareholders are companies with a stake in more than one big bank. Moreover, ownership figures for the second tier banks, Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited, Suncorp-Metway Limited and Bank of Queensland Limited, show they are also owned by the same organisations that own the big four.

When one looks closely at who owns the big four banks it becomes clear that there is a lot of common ownership, suggesting that those banks may not in fact be independent, competing entities.

Due to the complex nature of the legal structures of shareholders and ways that the various shareholders work together, it is virtually impossible to determine who really controls the banks. Many of the other minor shareholders in the banks also have HSBC, JP Morgan and Citibank, along with many other European and US banks as their major shareholders. This argument is often countered by stating that HSBC, J.P. Morgan and Citibank are only investing on behalf of small investors. What is of issue here is control and the prerogative of the funds to appoint a director to the board of their choice, not the investors. These figures are also consistent with a recent worldwide study showing that most of the world’s company equity is controlled by no more than 25 companies, of which many of these companies have equity in Australian banks.

One of the most interesting aspects that complement the cross-ownership in the big four Australian banks is the number of cross directorships in other foreign banks and financial institutions that exist in a wide manner. Studies have shown how even small cross-shareholding structures, at a national level, can affect market competition in sectors such as airline, automobile and steel, as well as the financial one.

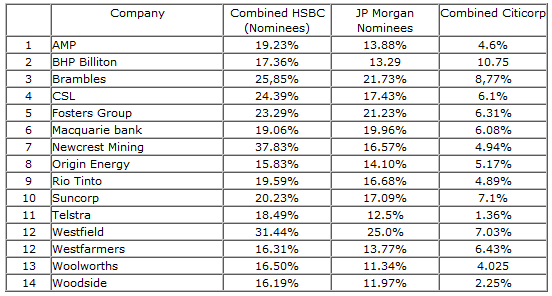

When one turns to corporate Australia, one will find that it is very similar to the banks. Both commercial and mining companies ownership are dominated by HSBC Nominees, JP Morgan Nominees, and Citibank Nominees as the top three shareholders of most companies. If one examines company directorships there is a tight cross-linking across commerce, banking and mining in Australia today. Commerce, banking and mining are now part of an oligopoly.

Table 2. Major shareholder of Australia’s largest public companies:

The reality is that much of Australia’s corporate landscape is owned by faceless people hiding behind big nominee companies that are virtually impossible to research. Not to mention global investment banks, insurance companies and the Commonwealth public servant superannuation scheme. Many companies have directors that are involved in media, banking, and politics, with many ex-politicians coming onto boards when they leave the parliament.

We have seen the close relationships between business and politicians over many governments. And Labor has been able to stay long in government with this accommodation with business interests, ever since Bob Hawke achieved an understanding with a significant group within the dominant corporations of Australia. Big business probably has greater influence at state level, where government can directly facilitate access to prime land and assets that each state controls.

Today in Australia, big business is able to practice what could be called “bully capitalism” where they dictate terms unfairly to smaller businesses. For example rents charged to tenants in large shopping malls are calculated as a percentage of turnover, with systems in place that allow landlords to audit tenant sales, where profit is virtually regulated. Supermarkets in Australia, now that a duopoly exists control over 90% of retail sales, have been able to increase profit margins from 20% in the 1970s to over 50% today.

With so much ownership concentration of Australian business and industry through skilful fund control and use of company law and cross directorships, a very few people can exercise great influence over the Australian economy. Many company boards and directors can operate without much accountability. As the recent Jonathon Moylan case has shown, any statement about a company can easily manipulate share prices and make profits or losses of hundreds of Millions of dollars instantly.

The potential to easily manipulate share prices is there on a huge scale. HSBC Nominees, JP Morgan, and Citicorp Nominees are the 1st, 2nd and 4th largest shareholders in the Australian Stock Exchange as well.

The great myth is that Australia is a competitive economy. Most of Australia’s largest companies have either monopolies or exercise some form of oligopoly.

For example:

- BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Woodside Petroleum, Newcrest Mining, Fortescue Metals and Origin Energy all have monopoly control over the resources they exploit.

- The four major banks exercise almost 90% control over all transactions in the economy and the smaller banks have the same shareholding as the ‘big four” as well.

- News Corporation controls over 80% of all metropolitan newspapers in Australia.

- Wesfarmers operate Coles, Bunnings, Target, Kmart, Officeworks in duopoly markets.

- Telstra has a near monopoly in telecommunications infrastructure.

- Woolworths operates in a duopoly with Coles.

- Westfield Group operates a unique group of shopping centres without competition, and

- CSL has an almost complete monopoly on all blood products.

- The top businesses in Australia do not exist within competitive environments and are therefore able to earn above average profits. This has potential consequences for local innovation, consequences for sustainable exploitation of resources, consequences for which industries survive and which industries are lost, and consequences for the cost of living for Australians, not to mention fairness and transparency in the marketplace.

About the author:

Murray Hunter has been involved in Asia-Pacific business for the last 30 years as an entrepreneur, consultant, academic, and researcher. Murray is now an associate professor at the University Malaysia Perlis, and consulting to Asian governments on community development and village biotechnology, both at the strategic level and “on the ground”. He is also a visiting professor at a number of universities and regular speaker at conferences and workshops in the region.

Murray is the author of a number of books, numerous research and conceptual papers in referred journals, and commentator on the issues of entrepreneurship, development, and politics in a number of magazines and online news sites around the world. He takes a cross-disciplinary view of issues and events, trying to relate this to the enrichment and empowerment of people in the region.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]