9th December 2011

By Anna Lekas Miller – AlterNet

“I have a confession to make,” said Jim Gerritsen, an organic seed farmer from northern Maine, “This is my first time in New York City. I had no good reason to come until today.”

Jim Gerritsen was one of several farmers, farm laborers, and food activists that came from across the country to the Farmer’s March this past Sunday—a rally and march designed to connect the struggles of rural farmers held captive by the corporate control of big agriculture with the Occupy movement in New York City.

The march began with music and a rally of speakers in La Plaza Cultural, one of New York City’s many community gardens, with over 500 rural farmers, urban farmers, food labourers, community activists and former occupiers—some wearing overalls and straw hats, and others wearing “we are the 99%” buttons.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

“I am here today to let you know that America is broken,” Gerritsen continued, addressing the diverse multitude. “The corporate control of our government and our economy—and the joblessness that it is creating—is directly related to the corporate dominance of big agriculture and the quality of food that you are getting.”

In addition to being a farmer, Jim Gerritsen is the President of the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGTA)—which this past spring filed a lawsuit with Monsanto, the corporate giant that controls 93% of the soybeans and 80% of the corn growth in the United States. Since March, over eighty-two other seed businesses, trade organizations, and family farmers—representing more than 300,000 people—have joined in the lawsuit, fighting the corporate monopoly of genetically modified seeds that are crushing organic farmers out of business and giving consumers little choice over whether or not their food is genetically modified.

Monsanto is not the only monopolistic offender—though it is one of the most influential through the extreme prevalence of corn and soybean chemical ingredients in processed foods. Four firms now control 84% of beef packing and 66% of beef production—over the past thirty years, the farming sector has lost over 90% of their pork producers, over 80% of their dairymen, and over 40% of their ranchers. Farmers are being forced into bankruptcy by corporate conglomerates.

Destroying jobs and economically devastating small farmers is only one element of the food industry’s particular strain of corporate greed. Eradicating farmers in favor of corporate mass production pushes their unregulated, heavily processed food on consumers. In addition to having little choice to begin with, this food is far more affordable by merit of its mass production.

As a result, more and more people—especially in lower income communities—are experiencing the health affects of genetically modified fats and sugars. It is no coincidence that obesity is directly correlated to income level, and that cases of diabetes, hypertension, and other obesity-related illnesses are concentrated in low-income communities, and often communities of color.

The reality is, most ordinary consumers in the ninety-nine percent are more concerned with trying to live within their means than making consciously healthy decisions. Economically, it makes more sense to purchase a filling fast food hamburger, especially when it is the same price as fresh fruits and vegetables. In trying to live from day-to-day, consumers lose track of long-term health consequences of their decisions, fueling the corporate supply with their continual demand.

As corporations become conglomerates and crush and replace small farmers, healthy food quickly becomes a privilege, rather than a right. And when storms caused or worsened by climate change like Irene come along, small farmers pay the biggest prices. Many of upstate New York and tri-state area farms lost a huge percentage of their harvest this year–and, one speaker at the rally said, while the media declared the storm over because the city was spared, they found themselves vulnerable to fracking companies who wanted to move in onto the land.

In the past, the food movement—like many movements—has been seen as a fringe movement, especially among urban audiences. What happened on the farm stayed on the farm, and products like organic heirloom tomatoes were more of a symbol of green elitism, rather than a means of resisting the toxic corporate machine.

Then along came Occupy Wall Street—a movement that combines its roaring collective fury at Wall Street and its radical, idealistic design to merge previously marginalized progressive movements into a vision for a new society to build over our broken, unsustainable system. One of these demands is food. Not just any food—food that is produced outside of the corporate machine, simultaneously protecting the livelihood of small farmers and ensuring the health of its eventual consumers.

In the days of the occupation at Liberty Plaza, the cooks in the kitchen formed alliances with many local, sustainable farmers, making sure that all of the food that they prepared was free of genetically modified organisms. A group called Feed the Movement formed, collecting donations to pay small, local farms for their contributions and thereby supporting both the occupy movement and small farmers. Several additional groups, such as Occupy Big Food and the Occupy Wall Street Sustainability Food Justice committee, also emerged, using the language of greed, inequality, and resistance mobilized by the occupy movement to bring awareness to the corporate stranglehold on the food industry.

However, until Sunday—aside from the occasional deliveries and donations—there was no organized urban-rural solidarity between farmers and occupiers. Though many farmers, such as Jim Gerritsen, were politically mobilizing against the corporate machine, these issues remained largely absent from the initial discourse on corporate greed, financial fraud, and joblessness. In rural communities—often conservative land where the most pervasive discourse on the occupy movement was negative—it was difficult for rural farmers to see themselves in the media’s images of the urban ninety-nine percent.

The Farmer’s March—organized by urban farmers and food activists within Occupy Wall Street–began to bridge this divide. While local CSAs and greenmarkets have been forming connections between urban consumers and rural farmers for several years (and pushing to get food stamps accepted and improve access to these bounties for low-income members), this took those small connections and made them large-scale.

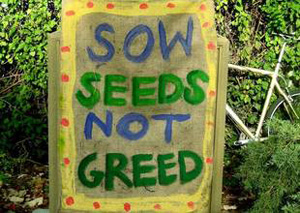

For the first time, rural farmers and this new crop of daring urban activists met one another in a massive way, exchanging stories of corporate greed and marching together to demand basic economic justice. The march culminated in a seed exchange in Liberty Plaza, symbolizing the ultimate peoples’ resistance to the food industry’s corporate machine.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]