By Steven Strong

Contributing Writer for Wake Up World

Our research team has been to, and returned to, many sacred and historic sites that have been ruthlessly vandalised. Unfortunately, the wanton disregard of Original engravings and stone arrangements, some thousands and often tens of thousands of years old, is so much a part and parcel of archaeology in Australia. So commonplace is this desecration of well known or easily found sites that our first priority has always been focused around preventing this outrageous disrespect; learning what the archaeology means and who was responsible for it must always take a back seat to its preservation.

For this reason, on occasions, I have been deliberately obscure when supplying details in relation to situation and geography. But fortunately, the site I will discuss today will never be vandalised. Its series of tunnels, and what lays beyond, would never have been stumbled upon by us or anyone else. It is only because artefacts researcher and spiritual archaeologist Klaus Dona sent us a photograph with the specific location marked out that we were now standing on this extraordinary site. Access to the site is not merely difficult; that would be a gross understatement. There are extremely steep slopes to negotiate and an entrance that betrays nothing to even a trained eye, except that advancing forward is fraught with real and present danger.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

Our first investigation was far briefer than what was needed. But we had two sites to examine on that day, and as this one was the unknown part of our day, more time was dedicated to the other site which promised tangible returns. Even getting to this site was a distraction of some magnitude, and maintaining balance while descending was a feat of its own. But the final stride to gain entrance was a thought-provoking effort; a four metre drop with no less than two metres to straddle across to the only foothold, followed by swinging the other foot up the slope and aiming at the dirt floor at the front of the tunnels. It was an action deserving of some forward planning. Fortunately those aboard were agile of foot and adventurous of spirit, and all of us managed to negotiate the divide.

With the exception of myself, the rest of the party was focused on finding an entrance of some sort. From the information we were provided, we knew the tunnel led deep inside. But we also saw the impact and damage caused by the mass of rock above, which was literally sliding down the hill and into this complex. By our estimation the there were two shafts/tunnels, one I could (being the thinnest) manage to get in nearly 10 metres before it narrowed to no more than 10 centimetres. I could see that the gap continued inwards and appeared uniform and quite long, but no-one in our group could advance any further.

The rest of the team were not deterred and sought out other means of entrance, but I went back to one section of the tunnel which measured close to 5 metres. We all agreed that the wall was so similar to the ancient walls in Chile and Peru. The joins were so precise that only the thinnest of twigs could be inserted 15 – 20 cms into the widest gap between these shaped rectangular sandstone blocks. There are four horizontal layers of sandstone blocks, each layer laid perfectly flat with a flat sandstone shelf of considerable dimensions and tonnage sitting atop this supporting wall. I tried to identify a possible geological process that could create such a complex and intricate alignment but came up empty every time.

In some respects our limited time on site was a blessing. I really had nothing to offer bar trying to make sense of what was obviously a wall built to take the weight of the rock shelf, along with the huge accumulation of shaped rocks with sharp edges, flat faces and ninety degree angles. The technology needed to construct it cannot be found in any Original tool-kit, or so the experts claim. Either way for now, it was time to walk away and return to measure and analyse it on another day. Which I did.

It took another four months before timing and finances allowed a return visit. Getting to the entrance seemed even more dangerous than before, or I was getting older. Despite a decidedly longer pause – a pause that was heightened by visions of what a poorly placed right foot could lead to, coupled with the apparent ease with which my companion on site, Ryan Mullins, casually breached the chasm – I did remain in tact and vertical.

This time we had no intention of finding a way in; all we were interested in was that one wall. Anything else that may have cropped up was merely an afterthought. Since our last visit, the damage created due to compression from above was even more evident. As before, so many of the rocks laying on the floor and positioned above, sometimes precariously, were shaped and cut. But this was more of the same and only reinforced what we already knew to be true; that this construction was not a natural formation.

The wall was still there and none the worse for wear. But that will change in time. The biggest shock was my inability to perform more than one task. It was so obvious the other three walls were always there. What wasn’t immediately apparent was how alike the walls actually were; the angles and measurements indicated a precision and repetition that could only come about through human hands and a metal blade.

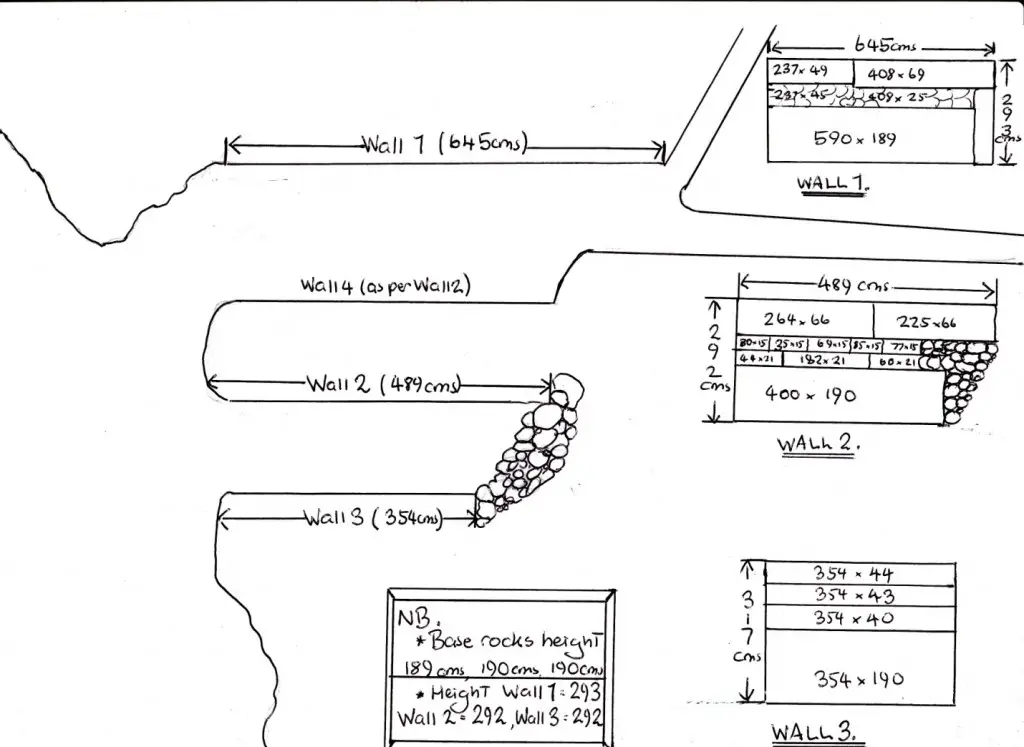

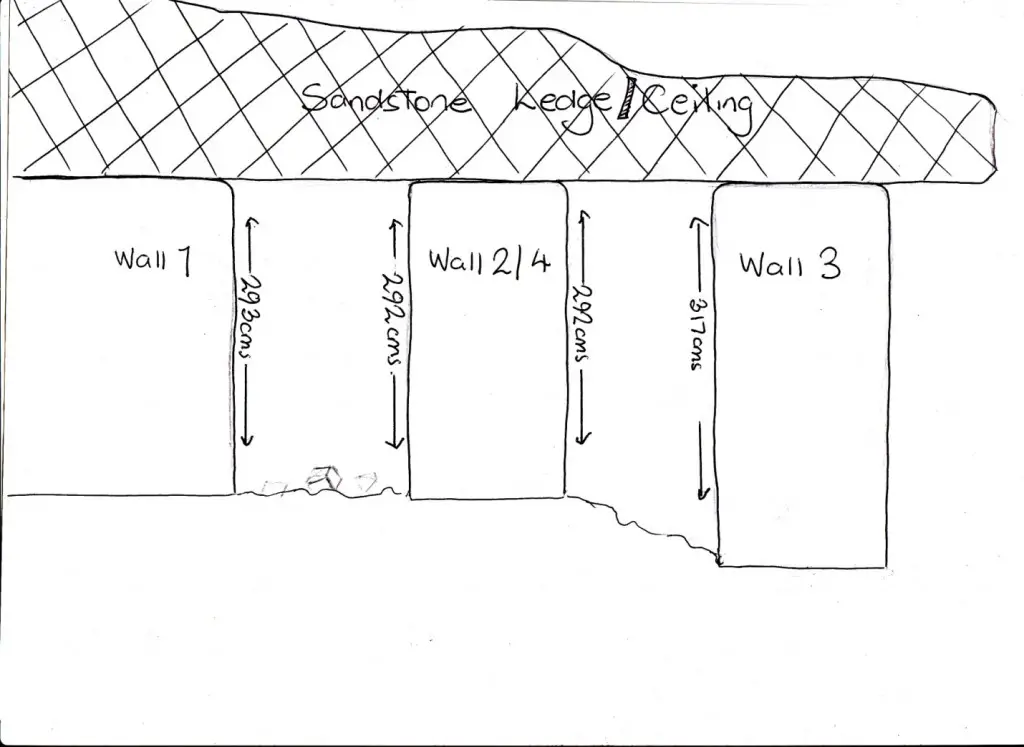

The three base rocks vary slightly in length, but in height there is no more than a one centimetre difference. Wall 3 is 190 centimetres high, Wall 2 is exactly the same and Wall 1 is one centimetre smaller at 189 centimetres. It is remotely possible that this is merely a coincidence, but there is more than one match at hand. Wall 1 and Wall 2/4 form what we suspect to be the main entrance, the floor between them is almost perfectly level, as is the rock shelve above. As such, it should come as no surprise that Wall 1 measures 293 centimetres in height, while Wall 2/4 is one centimetre shorter at 292 centimetres.

Being beneath and outside the main entrance, thus possibly acting more as a support for the two inner walls, Wall 3 is positioned down the slope and had to be built higher to support the weight of the 180 degree flat roof. This wall is 317 centimetres high and 354 centimetres in length. Being the furthest from the massive block of sandstone pushing against Wall 1, Wall 3 exhibits the least damage. All four layers of blocks that make up Wall 3 are complete, the bottom foundation stone is 354 x 190 cms, and the three layers above are basically of the same dimensions. The stone above the base block measures 354 x 40 cms, above that it is 354 x 43 cms, and the top stone (which takes the considerable weight of the sandstone above) is almost identical measuring 354 x 44 cms. Each shaped block is level at top and bottom, creating an almost seamless join.

To begin with, Wall 2 was all there was, and as it was with Wall 3, was made up of four layers. Constructed two metres up the slope, the foundation stone is exactly the same height as Wall 3 but 46 cms longer (400 x 190). In total the wall is 292 cms high and 489 cms at its longest point. The three horizontal layers above are not as high as those in Wall 3 and need to compensate for the 25 cm rise in the floor level so that this wall can share the load of the flat sandstone shelf/ceiling with Wall 3. The second level is made of two blocks, one 44 x 21 cms and the adjoining block 182 x 21 cms. The third layer is made up of five rectangular rocks, 20 x 15 cms, 25 x 15 cms, 59 x 15 cms, 65 x 15 cms and 77 x 15 cms. Being quite narrow it is quite possible there may have been two or maybe three blocks when originally constructed, but due to age and slippage above, these rocks could have cracked and split. The two capstone rocks above are much thicker and obviously separate to begin with, measuring 264 x 66 cms and 285 x 66 cms.

Of particular interest, and the primary focus of this excursion into country, was that the lines and seams evident on the face of Wall 2 span around the corner and along the face of Wall 4. It is for that reason that we saw no purpose in measuring this wall, they are identical to Wall 2. Moreover, we detected between layer two and three what looks suspiciously like mortar.

As we downed tools and pencils and began to walk away, we did so with mixed emotions and an uneven scorecard. Although fully satisfied with what was measured, recorded, drawn and deduced, when we paused and looked back, my companion and I both felt compelled to raise the same issue: the incredible weight of the overlaying sandstone shelf sitting atop three supporting walls. Flat is flat, and 180 degrees is 180 degrees sitting on a 45 degree slope. The three walls take the weight evenly and the rocks share angles, edges and measurements well beyond the realm of coincidence.

The real problems for any critic claiming this is all an unusual instance of natural geological processes are that the degree of the descent (approximately 45 degrees) is in contradiction with three straight parallel walls, and the sheer quantity of rocks with straight lines and right angles that form this entrance. If hundreds of tonnes of sandstone was sliding down the hill, any stationary rock, no matter what the size, will experience pressure in greater degrees increasing from bottom to top. As such, any resulting fractures should not run in straight lines and right angles. Straight lines are in direct opposition to the spread of force from above.

In our opinion there is only question left to determine: before or after? Were the walls built first then the rock platform placed on top, or was the shelf already jutting out with the walls and tunnels fashioned around and into the existing sandstone? Whatever the answer, it is clearly ancient and was constructed through the application of tools and technology supposedly not present in Australia before the British Invasion.

Unlike many other sites, the hazards of access and severity of the slope (standing upright unassisted is nigh on impossible) guarantee that vandals and those lacking cultural respect will never find this sacred place. The greatest problem is not arrogance but gravity, which has its own agenda. The time will soon come when the remaining ten metres of tunnel will narrow and seal, the wall bearing the brunt of this descent is beginning to crack and crumble, and no doubt Walls 2 and 4 will eroded down the same path.

In closing, we will briefly examine the most pressing issue: who made this? There is no less than 19.77 metres of wall underneath a massive sandstone shelf that just shouldn’t be there if standard texts and curricula are correct. At the very least, metal blades and refined masonry skills are essential to its construction, even if it was built on a flat platform. The difficulties in construction are magnified many times over on a slope with such a dramatic incline. We have already identified many artefacts, engravings and constructions in the immediate area that bear an ancient Egyptian influence or input, and it is possible they were responsible. As radical as that may appear, we regard their involvement as the more conservative option of all possible explanations.

When Klaus Dona directed us to this site, we were successful. Then he sent us another out-of-the-way location to investigate, and once again, another success – we actually found something even more amazing (I’ll more on that site soon). The problem is: two out of two sounds impressive, but there are over 140 more sites yet to investigate in the same general area. There was something absolutely massive here; a huge complex of which these three walls at this site, and the walls and decidedly odd rock at the other site, are merely an opening gambit. Egyptian? Well it is possible, remotely so, but we are more inclined to look much, much further back in time – and to not so readily discount talk of the earlier civilisations of Atlantis and, particularly, Lemuria or Mu.

Irrespective of the merits of our musings, this construction is not natural, not made after the British Invasion but well before, and not created through the use of any version of Original stone and stick technology. These are facts not opinions. What also cannot be denied is that whatever was built in ancient times at this site in Australia opens up a new page in world history.

All photos © Ryan Mullins for Wake Up World.

About the author:

Steven Strong is an Australian-based researcher, author and former high school teacher. Together with his son Evan, his work is to explore the ancient story of the Original people, a narrative that was almost lost to aggressive European colonisation.

Steven Strong is an Australian-based researcher, author and former high school teacher. Together with his son Evan, his work is to explore the ancient story of the Original people, a narrative that was almost lost to aggressive European colonisation.

Edited and additional commentary by Andy Whiteley for Wake Up World.

This article © Wake Up World.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]