By Andy Whiteley

Contributing Writer for Wake Up World

On 23rd March 2013, Australia’s disgraceful track-record in ‘Aboriginal relations’ reached a new low as police arrested and charged Ramindjeri Elder and senior Original Law man Lance ‘Karno’ Walker following an impassioned interjection in the South Australian parliament during debate over the SA ‘Aboriginal recognition’ Amendment Bill. He was charged with interrupting a public meeting, disorderly behaviour, failing to cease to loiter, resisting police and property damage.

What transpired within the walls of the SA Parliament House that day certainly beg questions of the SA Police. But the implications of Karno Walker’s story go much deeper; the political context of these events call into question the standing of Australia’s Governments in state, federal and international law, and the validity of the Commonwealth Government itself.

This article will examine in detail the events of Mr. Walker’s arrest as well as the legal and constitutional challenges surrounding it.

Please note: The word ‘Aboriginal’ is used in this article only in direct quotations of persons or legislations. In the English language, the prefix ‘Ab’ negates the adjective it precedes – eg. abnormal (not normal) and absent (not present). Therefore, the word ‘Aboriginal’ can be defined as ‘not original’ and although it is commonly used, I prefer the more accurate (and respectful) word ‘Original’.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

Parliamentary Input?

Along with two other Ramindjeri Elders, Mr. Walker was a guest of the parliament, in attendance for the reading of a statement for the Original Tribal Peoples of Australia. The Weatherill government had called on Tribal Elders to attend parliament in relation to their inclusion in the State constitution, and several Original leaders, including Mr. Walker, accepted the invitation to contribute. Their statement was delivered to the parliament by Ann Bressington, Member of the Legislative Council (MLC) as part of the Bill’s passage through state parliament.

Mr. Walker interjected in parliamentary discussion after a parliamentary official incorrectly acknowledged the Kaurna people as the Original tribal people of the land the parliament resides on. According to Mr. Walker, “it is Ramindjeri country and always will be”.

Karno Walker elaborates:

“I was representing the Ramindjeri peoples who are members of the OSTF, and I am the Chairperson and spokesperson for Ramindjeri Heritage Association Inc…. It was at the invitation of Gunham Badi Jakamarra, Convenor of the Original Sovereign Tribes Federation (OSTF) to witness the reading of a Statement for the Sovereign People of Australia, which was going to be read by Ann Bressington… she acknowledged myself and my two Elders as Ramindjeri leaders.

“A male speaker then took his turn to give his speech; he… kept acknowledging the Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri people as custodians of the land we are standing on. I was shocked and outraged by this acknowledgement… Even though we [the Ramindjeri] have done everything to the demands of the Federal Native Title Court and had to prove our unbroken bloodline… they are still continuing to recognize the people who do not belong here… who has not yet proven the ties or blood line to Ramindjeri land which they are claiming in their Native Title claim…

“I remember being asked to sit down twice before being asked to leave. I refused… as this is a place to talk and be heard. I wanted to finish what I was saying as it was very important to me and my people, and wanted it down on record. I am very passionate and committed to proving this is Ramindjeri country for my people who do not get a voice. This is Ramindjeri country that we are on – our country, not Kaurna or Ngarrindjeri. That’s why it angers me so much…This is why I spoke out”

Following his interjection, parliament was suspended. Mr. Walker left the parliament chambers with parliamentary official Chris Schwartz and Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) Security staff. He was subsequently arrested by South Australian Police.

Conflicting Accounts

Mainstream media reports of the events that followed Mr. Walker’s arrest were few and far between. Amid the relative media silence, an SBS News report on the passing of the South Australian Amendment Bill described:

“…an outburst from the public gallery, with Aboriginal (sic) activist Karno Walker decrying the entire procedure as a sham… The outspoken Ramindjeri man’s refusal to leave saw matters adjourned while the chamber was cleared and he was arrested.”

While this description is vague at best, an affidavit provided by Karno Walker reveals further details of the day’s events. Mr. Walker claims he had willingly exited the parliament after the chambers were cleared, and stood speaking with officials and Security staff when was confronted by police officers.

“Security approached me… The Hon. John Gazzola then adjourned the proceedings and asked everyone to leave. Security remained standing with me, observing the people leaving. I was then approached by Chris Schwartz, now known to me as the Black Rod, who asked me to leave with him. At this time I was talking to two members of parliament who were still there after everyone else had left..

“I then agreed to walk downstairs with the Black Rod, we chatted all the way down stairs. We walked past members of the Kaurna and other community members. One member of the Kaurna community, Mr. Tauto Sansbury, commented “I agree with you brother” as we walked past him. “I was then standing talking to the Black Rod, telling him some Dreaming stories and discussing the meaning of Wirritjin – meaning black fellow and white fellow coming together and working together as one…

“Next thing I know… I was approached from behind and grabbed on my left arm around my elbow area. Not knowing who this was I pulled my arm away and raised it in the air. I turned to see three police officers there; they at no time identified themselves prior to grabbing me. By this time I realized they were there to arrest me. I said to them “you have no right to arrest me here”.

“One officer said I was disturbing the peace, another officer said I was failing to cease to loiter. At this point I turned away to say goodbye to the Black Rod and the next thing I remember is lying flat on my back, thrown down by 3 police officers in the centre of the hall… Two other police officers came to assist the 3 already present. I was then forcibly rolled onto my stomach, slamming my face into the marble flood and levered my right arm (which had been caught underneath me) out with a baton so they could handcuff me. This caused tremendous pain. I was then handcuffed.

“[Police] were instructing people… to stop filming this event inside Parliament House.”

A statement made by witness and then-Member for the SA Legislative Council, Ann Bressington, corroborates Mr. Walker’s account.

“Sitting of parliament was suspended at 5:05pm because Karno was interjecting from the gallery during the debate, voicing his opposition…

“I went upstairs to the gallery to walk downstairs with Karno. The Black Rod and a security guard were speaking with Karno and were preparing to escort him to Centre Hall. I walked down with them.

“Karno… was not abusive or aggressive. He was speaking with the Black Rod in Centre Hall. I went outside to wait for him and immediately 4 or 5 police officers arrived.

“A security guard came outside and said to the police “It’s OK, he is ready to leave. We don’t need your assistance”.

“The Police officer responded “We’d rather just go in and rip him out now”.

“The police went inside and I followed. I witnessed the police officers walk up to Karno from behind and grab his arms. Karno swung around and the police officers then threw him to the ground… I did not hear the police officers identify themselves as police officers.” [emphasis added]

Karno Walker was arrested by 5 police officers, taken to the City Watch House, charged and subsequently granted bail. Mr. Walker continues the story:

“I was then dragged backwards outside, down the steps of Parliament House in to the public. [My wife] asked one officer… what was going on [and] he told her to “F*** off, this has nothing to do with you”…

“Just before crossing Station St., both Police Officers Reed and Devlin threatened me saying they were going to bash me once we arrived at City Watch House… I was interviewed some time after by the arresting officers; this interview was both recorded and videod.”

Records of a medical examination conducted on Mr. Walker in the days following his arrest include details of “bruising on his left elbow… elbow pain and swelling… a graze on the bridge of his nose… some restriction of movement of neck… He has back pain… He has a loose tooth and has had a persistent headache that requires analgesia”.

SMILE! You’re on Camera! … and in Public

CCTV video footage of the controversial arrest and subsequent police interview have been obtained by Karno Walker under Freedom of Information laws, as have personal videos taken by bystanders to the event and other visual and testimonial evidence. For legal reasons, Wake Up World cannot release this footage to the public. Nonetheless, the weight of evidence suggests the outspoken Tribal leader caused no physical damage and calls into question the actions of the arresting officers – in particular the level of force applied, and the lawful standing of the police who apprehended him.

According to evidence held by Mr. Walker, he was speaking with DPS Security officers and The Black Rod in the security area after he exited the parliament chambers, caused no public damage and was not aggressive at that time. Police officers then entered the Hall and approached Mr. Walker from behind. One of the officers visibly grabbed the Tribal leader on the elbow. Surrounded by Police and Security staff, Mr, Walker turned to face the officer that grabbed him, and after a few moments of dialogue raised both arms in the air in a seemingly passive motion. Moments later, after further discussion with the primary officer, Mr. Walker was restrained first by the arms, then after resisting the grip of (notably) only one of two restraining officers – again, the primary officer – Mr. Walker was placed in a headlock and thrown by the neck from a standing position to the ground, face down, and restrained by three, then five officers. According to Mr. Walker, the officer was using unreasonable force in his restraint of his arm.

Personal footage supplied by onlookers to Mr. Walker’s arrest show the Original leader being taken down the stairs to Parliament House, backwards, then escorted, still backwards, to the Police van parked a block away.

Mr. Walker was taken to the Adelaide City Watchhouse where he was interviewed by one of the arresting officers. A recording was made of that interview and later obtained by Mr. Walker.

According to evidence held by the Walkers, the arresting officer allegedly stated:

OFFICER: I was tasked to Parliament House… the information that I received en route – there was a male inside making a disturbance. That was all the information I received. On arrival at Parliament House I spoke to several Security officers at the front door. … I approached you, touched you gently on the elbow as I saw that you were arguing with several security officers there. At that point you turned around and said to me “don’t assault me, don’t assault me” and proceeded to continue to argue with security guards and argue with us. I am unaware of why you were agitated there at that point…

If the arresting officer approached Mr. Walker from behind and handled him before identifying himself – and before being seen by Mr. Walker – surely that is deemed unlawful in itself. But if the officer did so without query or investigation, understanding only that “there was a male inside making a disturbance. That was all the information I received”, questions should be asked of the officer’s capacity to understand and diffuse a perceived disturbance situation.

According to Mr. Walker, the interview continued as follows:

OFFICER: now, when you were escorted into the security area… why were you standing in the personal proximity of several members of parliament security yelling at them.

KARNO: I wasn’t yelling at them, I was talking to them.

OFFICER: My allegation is that you were extremely agitated at this point…

KARNO: Please explain that word.

OFFICER: You were gesticulating with your hands… You were pointing at them. Gesticulating… When I approached you in the security gallery area, I saw that you had 2 clenched fists and were standing within the immediate personal proximity of several parliament security staff. By personal proximity I mean within a half a metre to metre of them, leaning forward toward them in an aggressive manner with aggressive body language…

According to evidence held by the Walkers, the proximity of DPS Security Officers to Mr. Walker at the time the Police officers entered the hall appears to have been at the discretion of Security, not Mr. Walker. Security staff escorted Mr. Walker to a corner of the Hall and stood by him at their own accord, and Mr. Walker stood upright while he spoke with Security, not leaning “toward them in an aggressive manner” as the Police officer allegedly stated.

In further contradictions, the “gesticulation” described in this statement is contradicted by evidence held by the Walkers, and does not seem to have intruded on the “personal proximity” of DPS Security; rather Mr. Walker’s elbow was tucked tightly by his side, his finger raised near his shoulder as he spoke. Allegations of “aggressive” “disturbance” behaviour are also contradicted by evidence of the general scene, as visitors and staff are seen visibly smiling and talking as they pass through the area. Furthermore, a description of Mr. Walker’s “clenched fists” as he first approached the scene contradicts an earlier description of Mr. Walker’s “gesticulating… pointing at” Security staff.

OFFICER: I approached you and touched you very gently with 2 fingers on your left arm, at which point you spun around to face me and stood to within half a metre of my personal proximity and held your index finger to within approximately 30 – 40 centimetres and yelling “don’t you assault me, don’t you assault me”. At that point I said “I’m saying hello” and that “the police are here”. At that point you continued on, arguing with the security people there. I then said loudly and audibly to you… “you are required to cease loitering…” [pause] I’ll start again. My direction to you was loudly and audibly “a breach of the peace has occurred. You are required to cease loitering from this area forthwith or you will be arrested…”

KARNO: I asked you a question… “Under what law?”

OFFICER: .. and you continued to argue with myself and other security people. And then I …

KARNO: I asked you “under what law? Under what authority?” – that’s what I asked you.

OFFICER: It’s under the Summary Offences Act. I’m not actually required to explain to you what law I’m using. The direction again was then repeated…

The apparent contradictions continue. Firstly, “I’m saying hello” is an inadequate (somewhat implausible) approach for an experienced officer to adopt in a potentially “agitated” disturbance situation.

Based on evidence held by the Walkers, the statement “you spun around to face me and stood to within half a metre of my personal proximity and held your index finger to within approximately 30-40 centimetres” is also in question; rather Mr. Walker turned on the spot to face the officer who touched him, the close physical proximity to the arresting officer determined by the officer himself, not Mr. Walker. Further evidence held by the Walkers suggests Mr. Walker pointed his index finger at the officer then gestured behind himself, over his shoulder with his thumb, indicating events/directions/locations to the officer – as Mr. Walker maintains.

The statement “At that point you continued on, arguing with the security people there” is also contradicted by the Walkers’ evidence, which indicates Mr. Walker addressed the officer who grabbed him as well as another Police officer who stood opposite, in similar physical proximity. Mr. Walker did not engage any further with DPS Security staff, who appear to have backed away from the scene by this time.

Most importantly, the statement “I’m not actually required to explain to you what law I’m using” is legally incorrect, raising genuine questions of the actions of SA Police.

South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953

Karno Walker was charged with interrupting a public meeting, disorderly behaviour, failing to cease to loiter, resisting police and property damage – under the South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953. At this point it is judicious to examine the laws relating to these charges.

From the South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953, Part 3-Offences against public order, Section 18A-Public meetings:

(2) Where, in the opinion of the person presiding at a public meeting, a person in, at or near the place at which the meeting is being held—

- (a) is or has been behaving in a disorderly, indecent, offensive, threatening or insulting manner; etc…

- (b) is or has been using threatening, abusive or insulting words; or

- (c) … has been obstructing or interfering with—

(i) a person seeking to attend the meeting; or

(ii) any of the proceedings at the meeting; or

(iii) a person presiding at the meeting in the organisation or conduct of the meeting,the person presiding may request a police officer, or the police generally, to remove that person from the place or the area in the vicinity of the place.

(3) A request made under subsection (2) must be complied with by an police officer present or attending at the place at which the meeting is being held. [emphasis added]

When a ‘disturbance’ occurs at a public meeting at which the police are not present, the police are authorised by law only to “remove that person from the place” at the request of the person presiding. The person presiding cannot authorise an arrest, and without witnessing the disturbance, nor it seems can police. In this case, evidence suggests Mr. Walker had willingly left the parliament chambers – the place of the alleged disturbance – before police arrived, and police had been instructed by DPS Security upon their arrival that “he is ready to leave, we don’t need your assistance”.

As parliament had already been suspended and any ‘disturbance’ thereby nullified, the police had no right to arrest Mr. Walker under Section 18A.

From the South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953, Part 3-Offences against public order, Section 18-Loitering:

(1) Where a person is loitering in a public place or a group of persons is assembled in a public place and a police officer believes or apprehends on reasonable grounds—

- … (b) that a breach of the peace has occurred, is occurring, or is about to occur, in the vicinity of that person or group…

the officer may request that person to cease loitering, or request the persons in that group to disperse, as the case may require.

(4) The police officer must, before making the request, advise the person—

- (a) that the request is being made under this section

(5) If, in response to a request by a police officer… a person of a prescribed class refuses or fails to state a satisfactory reason for being in that place, the person is guilty of an offence. [emphasis added]

According to Mr. Walker, police officers did not identify themselves as such upon approach, no request was made of him to leave the premises of his own accord, no advice was given to him about the Section under which such a request could be made, and no opportunity was given to “state a satisfactory reason for being in that place” – which he clearly had. Evidence held by the Walkers indicates only a brief dialogue between Mr. Walker and police, and supports his claim that such a detailed conversation did not take place. Further evidence suggests the arresting officer acknowledged that at least two of those four requirements were not met, despite knowing on arrival only that “a male was causing a disturbance”.

Given the specific requirements of this Section, evidence suggests the actions of police officers were not sufficient to lawfully enact Section 18.

From the South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953, Part 2-Offences with respect to police operation, section 6-Assaulting and hindering police

(2) A person who hinders or resists a police officer in the execution of the officer’s duty is guilty of an offence.

If a police officer has acted outside “the execution of the officer’s duty” by unlawfully enacting Sections 18 & 18A against Mr. Walker, subsequent charges of resisting police cannot legitimately be applied. Traking reasonable steps to resist the unlawful actions of another – even one who is wearing a uniform – is in fact lawful. Furthermore, evidence that Mr. Walker resisted the grip of only one of two officers does not reflect the motivation to resist, assault or hinder.

From the South Australia Summary Offences Act 1953, Part 3-Offences against public order, Section 7—Disorderly or offensive conduct or language

(1) A person who, in a public place or a police station—

- (a) behaves in a disorderly or offensive manner; or

- (b) fights with another person; or

- (c) uses offensive language,

is guilty of an offence.

Strangely, the Act does not specify what constitutes “disorderly or offensive” conduct (or language), thus leaving the judgement of offensive conduct open to subjective interpretation. In this case, the alleged actions of police suggest a limited or impaired capacity to subjectively determine the conduct appropriate to such a situation. According to evidence supplied by the Walkers, the Officer was unable to provide a definition of “agitated” – another subjective term. Thus, in context, this charge must be viewed as just one in a series of faulty charges.

But that’s only half the story…

Legal Recourse

Following the events of March 2013, Karno Walker undertook legal proceedings to obtain evidence of these events, including CCTV footage from Centre Hall and the Adelaide City Watch House to which he was taken. But details provided by Mr. Walker suggest that even this process – his legal recourse under whitefella law – was met with further questionable behaviour.

Despite numerous requests made by Mr. Walker, documented in accordance with applicable criminal justice procedures, it took over 2 months and a Court Order before prosecutors finally disclosed to Mr. Walker details of the evidence they intended to present against him. And according to Mr. Walker, when that information was finally received, the key piece of evidence – the CCTV footage of his initial arrest – was missing, despite having been referenced in the charges that were laid against him.

According to Mr. Walker’s affidavit dated July 15th 2013:

“[I] attended Magistrate Court on 30 May, 2013… Up to this date I had not received any evidence the prosecution intended to use for their case against me even though… on the 6th of May 2013 I faxed the requested written request their office and… the Office acknowledged that they had received the request.

“On 30th May 2013 Justice Bolton… made orders that the prosecution make me full disclosure of any and all evidence the prosecution intended to use in their case against me… Later that day… I received a phone call from prosecution asking us to pick up the evidence which was placed in an (sic) large brown envelope and left at… Police Headquarters. In that envelope were 5 police affidavits and 4 affidavits from members of Parliament House staff as well as 1 Disc containing footage from within the City Watch House ONLY. There was no footage from Parliament House which we also requested.

“The CCTV footage within parliament house has been referred to within the Complaint laid by the Police at page 4, paragraph 8. To this date, 15 July 2013, this footage has not been disclosed to me.”

The CCTV footage was finally provided to Mr. Walker after a Court Order was issued.

Viewed in isolation, the apparent force used by police officers and the charges levelled at Mr. Walker raise questions of at least some of the police officers involved. But when also considering the apparent reluctance and lack of procedural adherence in relation to Mr. Walker’s right to evidence, questions must also be asked of the the SA Police Force administration and Department of Parliamentary Services (Security), the department responsible for Government CCTV infrastructure and data.

Notably, similar questions are already being asked of DPS Security. Last month, NSW Senator John Falkner accused DPS Head Carol Mills of breaching rules of privacy and parliamentary privilege after it was revealed that images captured within parliamentary offices were unlawfully used. While “Senator Faulkner, a former defence minister… was [in 2011] leading an inquiry into parliamentary administration from government”, Australian Federal Police investigators were given access to footage from the parliament office’s CCTV cameras, including images of the press gallery and visitors to his offices – meetings which are protected under parliamentary privilege. Senator Faulkner, who was first elected to the NSW senate in 1989, described this as a “most serious breach”. According to the Sydney Morning Herald report, a subsequent “hearing was told that the DPS was “toxic”, “paranoid” and “deeply dysfunctional” with a culture that ignored bullying and harassment.”

Mark Aldridge is an independent SA parliamentary candidate and spokesperson for the Australian Alliance, an organization of independent candidates, advocates, lobbyists and community members. Referring to the charges laid against Mr. Walker, he says:

“The sworn statements the prosecution produced in their brief of evidence are clearly purgered evidence as the content of these statements is clearly and demonstrably contradicted by the Parliamentary Security CCTV which initially, the prosecution deliberately sought to conceal until they were forced to produce this evidence…

“Also the defence has witnesses… whose evidence starkly contradicts the police… a member of the Legislative Council of SA Parliament who has produced … evidence that the lead police officer stated unequivocally his intent to commit an illegal act of provocation – amounting to a criminal act.

“The only lawful option the prosecution have, that is procedurally correct is to “lead no evidence” whereupon the court would dismiss the charges.”

While Mr. Walker pursues avenues of lawful recourse, questions still remain unanswered:

- Why would SA Police arrive after a disturbance has already ceased, where no direct threat to public safety still exists, and pursue an aggressive course of arrest? Particularly with a respected (however outspoken) public figures like Karno Walker?

- Why was evidence seemingly withheld from Mr. Walker and his legal counsel, his right to disclosure of evidence upheld only after a lengthy legal intervention?

- And why have charges against Mr. Walker not been pursued by police?

Constitutional Context

The Ramindjeri’s claims of Original sovereignty leave the Commonwealth in a very tenuous constitutional position, and as the long-time spokesperson for the Ramindjeri nation, Karno Walker undoubtedly embodies long-standing questions of legitimacy which the Commonwealth Government would rather not answer. As the Original tribal people of this land, the Ramindjeri – like many other Original tribes – assert that their peoples’ sovereignty was never consentingly surrendered to the British, and therefore stands unbroken – and recognized as such in international law.

Did the challenges Mr. Walker poses to the constitutional foundation of “the Australian Way” motivate his apparent mistreatment at the hands of the criminal justice system? Whatever the motivation, by arresting Mr. Walker under Commonwealth law, it appears his rights under a United Nations resolution may have been violated by police, further complicating matters for Commonwealth authorities. Let’s examine at the Constitutional matters first.

According to a Notice of Constitutional Matter submitted by Mr. Walker to the Federal Court of Australia in September 2012:

“The Ramindjeri Declares it has never vested its’ Sovereignty nor Dominion over its’ lands and people to the Crown… [nor] by way of a FULLY INFORMED CONSENT, granted or otherwise acquiesced their Sovereignty and dominion over themselves, their lands, law, heritage and culture to the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and or the STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA…

“The Constitutional issues that have arisen are:

“… whether the parliaments of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and or THE STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA have legislative competence to regulate and or effect and or override the laws, rights, culture, heritage, lands, men, women and or children of the Ramindjeri Tribe.

“… whether the Constitutions of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and or THE STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA contain/s ANY element/s of sovereignty sufficient to override the Sovereignty and dominion of the Ramindjeri Tribe over themselves and their lands, their law, culture and heritage.”

In essence, the Ramindjeri – among the world’s oldest continuing civilizations – is asserting its ongoing sovereignty, challenging both the notion of consent and the right of the Commonwealth to impose its law upon an existing civilization.

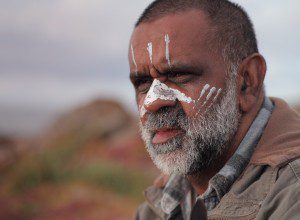

While Australian mainstream history often downplays the extent of abuse the Original tribes suffered at the hands of invading Europeans, the inhumane treatment imposed upon the Original peoples of Terra Australis – an example of which as pictured left – cannot be considered as ‘consentual’ by any twisted interpretation of law or imagination. It was brutal. Governments of the day “made special laws” to govern the Original tribes people, dispossessing them of their land, breaking up communities, herding many into slavery reservations, and systematically breeding out the Original blood lines.

Under these circumstances, the Ramindjeri cannot possibly have met legal conditions of consent under Commonwealth law; slavery and consent are mutually exclusive.

Moreover, prior to the passage of the 1967 Australian Referendum, Original tribal people were not recognized by law as equal (and therefore consenting) subjects of the Commonwealth. Until that time, equal legal capacity had not been extended to Original tribal people. As former Prime Minister John Howard once stated, “the 1967 Referendum was about treating all Australians equally”.

Section 51 of the pre-1967 Constitution stated:

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to…. the people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.

Section 127 stated:

Aborigines not to be counted in reckoning population… In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.

While it is clear the actions of the Commonwealth Government were not consented to by the Original tribal peoples, Mr. Walker’s legal action raises another unanswered question — does the Commonwealth of Australia have the authority “sufficient to override the Sovereignty and dominion” of the Original tribal peoples?

It appears the answer is also ‘No’.

SA Constitution (Recognition of Aboriginal Peoples) Amendment Bill 2012

The circumstances leading to Mr. Walker’s arrest centre around the passing of the Constitution (Recognition of Aboriginal Peoples) Amendment Bill 2012, an Act to amend the Constitution Act 1934.

According to an SBS News report, the “South Australian Parliament has passed a Bill recognizing past injustices and acknowledging Indigenous citizens as the first owners and occupiers of the state”.

While on the surface this may sound like a socially progressive move, the response within political circles has been understandably mixed.

Social Justice campaigner Tauto Sansbury says:

“While the proposed Act may be well-intentioned, it creates a dangerous sleight-of-hand scenario. It creates the impression of a tangible benefit to Aboriginal (sic) people, while in practical terms their position is not materially advanced. The feel-good emotions it is calculated to create in the wider community tend to mask the real plight that Aboriginal people experience in society. The issues of poverty, poor education, health, housing and over-representation in the criminal justice system are matters to be addressed prior to the window-dressing of an amendment to the South Australian constitution.”

Greens MP Tammy Franks continues:

“Let us not forget the more recent history where the peoples of over 40 nations within the mapped boundaries of this State, and indeed the several hundred nations across the continent of this island, were treated as invisible, as sub-human and as somehow lesser. Let us remember there was a past where policies and practices sought to assimilate and eradicate the very existence of the first peoples; where those who invaded or settled were guilty of murder, of rape, of poisoning, of stealing, of paternalising and more recently I believe patronising.”

Dignity for Disability MP Kelly Vincent says recent government policy decisions have stripped Original people of rights, and fears that will continue while the SA government cloaks itself in credit for its constitutional achievement.

“While I am proud to be taking a step forward with the passage of this Bill today, I am more concerned that it will not be long before we see this government’s selfishness and lack of respect and cooperation drag us back two steps again.”

Herein lies the problem.

The limited paradigm imposed by government and media on the discussion of ‘reconciliation’ has led most white fellas – even well meaning ones like Ms. Vincent – to believe that enveloping the Original peoples in the legal system that systematically decimated their ancestral cultures is “a step forward” in reconciling this offence. But consider –

Would you willingly consent to the laws, rules, systems and priorities of another society that dispossessed your ancestors – and therefore you – of your culture, land and heritage?

Beside paperwork, what is actually being done to honour, revitalize and preserve Original culture, knowledge, language, ancestral land and sacred sites?

If reconciliation is genuinely the goal of Government, why is it officially (and paternalistically) ‘recognizing’ the Original peoples, but not also seeking an equivalent recognition in Original tribal law?

Most importantly, why does the Government’s recognition of the Original tribal people appear to be so selective?

A perfect example of this selectivity is found on the official application form for Abstudy, a Government allowance offered to students of “Aboriginal (sic) or Torres Strait Islander” descent. Under the personal details question “What is your Marital Status?”, the proforma selections include the following option:

“Married or recognized as married under Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander law:

Other benefit application forms, including the Claim for Parenting Payment and Disability Support Pension forms, also ask applicants for their ‘Aboriginal (sic) or tribal name’.

In reality, the Australian Government recognizes the validity of “Aboriginal law” by classifying as “married” any Original persons recognized as such under Original Law, and by requesting Tribal names for official government records. But in matters directly relating to the Original peoples’ rights and sovereignty, it appears the Australian Government prefers to deny the validity of Original law, and continues to enforce Commonwealth law on the Original peoples – crucially, without their consent.

Lawfully speaking, 200+ years of systemic abuse neither extinguishes nor acquires by treaty the Original Tribal Peoples’ sovereign rights to their lands, waters and natural resources and airspace above their lands. And now, just as Australian Government branches are seeking to incorporate the Original peoples in their Constitutions (instruments of rule and regulation of those who consent to them), many tribal peoples including the Ramindjeri are instead demanding the lawful recognition of their own continuing sovereignty, as recognized by Commonwealth law and UN convention, and refusing – still – to consent to the imposition of outside rule.

The Amendment Bill has No Legal Affect

Of course, Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda has congratulated the South Australian Parliament for passing the Amendment Bill, calling it:

“… a necessary and missing overdue piece of our national identity. The Constitution (Recognition of Aboriginal Peoples) Amendment Bill 2012 not only acknowledges and respects Aboriginal peoples as the State’s First Peoples but also acknowledges that South Australia’s laws were developed without proper recognition, consultation or authorisation of South Australia’s Aboriginal peoples.”

Notably the Amendment Bill contains an important caveat – the Constitutional recognition of the Original peoples has no legal effect. So while this Amendment effectively acknowledges centuries of physical, cultural and spiritual abuse, that’s all it is; an acknowledgement. The Amendment cannot be used for any legal compensation or land claim. But more importantly, just like Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s famous “Sorry”, the Bill goes nowhere toward helping restore the “self-determination, freedom and independence” of Original people and communities affected by generations of crimes against them. It provides no remedy or recourse for centuries of exploitation, only “acknowledgement” – of course, the unspoken implication being that no remedy or recourse is actually warranted.

Unfortunately, most whitefellas in this country seem to think the process of ‘reconciliation’ is done and dusted – no doubt the intended effect of these “official” acknowledgements.

While no legal recourse is available to the Original peoples as a result of the SA Amendment Bill, there are other legal and constitutional factors that may force the state and federal Governments of the Commonwealth to finally honour the sovereign rights of the Original tribes. To do otherwise would create a Constitutional dilemma that renders those very Governments invalid.

Letters Patent

Unique to Australia, Letters Patent is a legal instrument of the monarch, issued in the form of a written order. Letters Patent is generally used to grant an office, right, title, or status to a person or entity. The terms of Letters Patent can only be amended or revoked in law through the same means in which they were enacted – another Letters Patent issued at the order of the monarch.

In 1836, King William the Fourth issued Letters Patent declaring that Original people should not be deprived by settlers of the occupation or free enjoyment of their lands. While Letters Patent 1836 has never been honoured, in word or in principle, nor has it been amended or revoked. Therefore, the protections provided to the Original peoples via Letters Patent 1836 stand unaltered in Commonwealth law. Still, 179 years later, the Ramindjeri and other tribal representatives are calling for their rights as the land’s Original custodians to finally be honoured.

During the passage of the South Australian Amendment Bill, Opposition MP Terry Stephens downplayed the significance of Letters Patent as an “example of good intentions unfulfilled”, and suggested that diligence is required to prevent the recent amendment to the state constitution from ending the same way. But while Government representatives may be quick to dismiss the King William’s 1836 declaration as mere “good intentions”, not surprisingly, such a dismissive interpretation of the laws enacted via Letters Patent 1836 has not been well received.

Karno Walker explains:

“Why should we the Ramindjeri tribal people of the land and other true tribal people come under the Australian & South Australian constitution, just to have lesser rights? We already have sovereignty which the government and the crown refuse to recognise even today. Sad that we are still not recognised even today in 2014. as equals, as a part of Wirritjin*. Yet they expect us to abide by the laws they invent without consent of the tribes, and they don’t even abide by their own laws like Letters Patent”

[*Wirritjin: black fella white fella Dreaming]

Letters Patent is one of the most important prescriptive instruments of government in Australia. The Constitutional Amendment (Recognition of Aboriginal Peoples) Bill acknowledges the Letters Patent mechanism. The highest office in Australia, the Office of Governor General, is enacted by the monarch by order of Letters Patent. From there, a Governor General is appointed to the Office of Governor General, and he or she enacts Government. Put simply, without Letters Patent there is no Government.

Because the existence of Commonwealth Government and those of the States relies on the absolute integrity of Letters Patent, the SA Government’s decision to disregard the laws enacted via that mechanism on a selective basis (one of convenience) effectively invalidates all federal and state Governments of the Commonwealth of Australia.

If Letters Patent can be disregarded without consequence – and 179 years of continued legal precedent says that it can – so too can the Office of Governor General, the Commonwealth Government and all agencies therein.

If the Commonwealth Government is to retain any Constitutional legitimacy, the lawful right to unimpeded “self-determination, freedom and independence” of the Original tribal people must be honoured in accordance with Letters Patent 1836.

Australia’s lawmakers can’t have it both ways.

Needless to say, this creates quite a Constitutional crisis. For Government to selectively disregard Letters Patent as they relate to “the rights of any Aboriginal (sic) Natives” invalidates the integrity of the instrument through which Government in Australia is created.

Notably, the Letters Patent establishing the Province of South Australia provide further legal protections for the rights of the Original peoples; protections that have also not been upheld:

… nothing in those our Letters Patent contained shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said Province to the actual occupation or enjoyment in their own Persons or in the Persons of their Descendants of any Lands therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives

United Nations Resolution 2625 (XXV)

Without question, the Governments of Australia have disregarded Commonwealth and State laws relating to the treatment of the Original tribal people for generations. But the legal implications extend further than the Commonwealth; the sovereignty of the Original tribal peoples is protected by the charter of the United Nations.

On 24 October 1970, United Nations Resolution 2625 (XXV) was enacted: Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Australia is a signatory to this resolution. In short, the Resolution protects the principle of equal rights and self-determination of the Original tribal peoples:

By virtue of the principle of equal rights and self determination of peoples enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, all peoples have the right freely to determine, without external interference, their political status and to pursue their economic, social and cultural development, and every State has the duty to respect this right in accordance with the provisions of the Charter….

Every State has the duty to promote through joint and separate action universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms in accordance with the Charter…

The establishment of a sovereign and independent State, the free association or integration with an independent State or the emergence into any other political status freely determined by a people constitute modes of implementing the right of self-determination by that people…

Every State has the duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples referred to above in the elaboration of the present principle of their right to self determination and freedom and independence.

Article 37 continues:

“Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as diminishing or eliminating the rights of indigenous peoples contained in treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements.”

So why are the lawful protections provided to the Original people through mechanisms of Commonwealth, State (Letters Patent) and International law (United Nations) so routinely disregarded by the Governments of Australia? In this tenuous political context, was Karno Walker’s arrest symbolic of the legal and ethical battle being fought between the Original sovereign tribes and the Australian Commonwealth establishment?

Native Title

The Ramindjeri’s claims of sovereignty pose incredible constitutional challenges to the Commonwealth of Australia. Rather than consenting to the imposed rule of the invading Commonwealth and applying to the Government to grant them limited land rights and recognitions within that system, the Ramindjeri have undertaken legal actions that assert the ongoing sovereignty of the Original tribes and challenge the right of the Commonwealth to impose its laws upon the Original sovereign tribes – now or ever.

As the Chairperson and spokesperson for Ramindjeri Heritage Association Inc, Mr. Walker has engaged in lengthy legal proceedings to have his peoples’ sovereign heritage and land rights recognized, and protected accordingly. In particular, dispute arose in 2010 between representatives of the Ramindjeri tribe – who have asserted their uninterrupted tribal occupation of the disputed area to the Australian Federal Court – and the Kaurna – who have given up any sovereignty claim, choosing instead to apply to the Commonwealth Government to grant them limited ‘Native Title’ rights under Commonwealth law.

According to Mark McMurtrie, spokesperson for the Original Sovereign Tribal Federation (OSTF):

… [the] Kaurna are claiming Native Title. The Ramindjeri are claiming Sovereignty. The differences between the two positions is light years. Sovereignty needs no explanation, one would hope, however, Native Title needs significant clarification to distinguish it from what it is said to represent when touted publicly…

Native title is a form of title issued by Crown.. government bodies to ‘Aboriginal’ groups or people over land that has been ‘colonised’. The process of Native Title requires an applicant to admit they are a ‘Traditional’ owner; the term Traditional qualifying the word ‘owner’. For this reason we need to properly comprehend exactly what the term ‘traditional’ means at law.

The term Traditional comes from the Latin ‘Traditio’ which means one who has SOLD his land to another. This is the root word for other terms like trade, traded, trading, etc….

The legal implications of the term Traditio means:

“TRADITIO. Lat In the civil law. Delivery; transfer of possession; a derivative mode of acquiring, by which the owner of a corporeal thing, having the right and the will of aliening it, transfers it for a lawful consideration to the receiver. Heinecc. Elem. lib. 2, tit. 1, § 380.”

… Accordingly, one who is a ‘Traditional Owner’ is one who was the owner but has sold his interest to another…. This is the Crowns’ ONLY means of acquiring Tribal lands, and in the manner it is employed represent[s] serious extrinsic fraud on the part of the Crown and its minions and parliaments.

… This usurpation of the Tribes Sovereignty is in direct contravention to Queen Victorias’ Order in Council of ~2 August 1875 which, in clear terms, prohibited the prohibited the UK and its’ minion parliaments here from ‘extending or construing to extend sovereignty or dominion’ onto this continent or the Pacific Islands. Those Tribes/peoples asserting their Sovereignty against the colonising peoples are protected in such efforts by this instrument. An instrument relied upon by Australia and other UN Member States to justify their actions against various other colonial governments in the past.

This brings us to the core of the Original sovereignty debate in Australia. After generations of systemic abuse, the Ramindjeri refuse to concede their sovereignty. (Would you?) And their declarations of continued sovereignty pose real challenges to the constitutional foundation of the Commonwealth, and throw into question the integrity of its Native Title laws – among other things. Undoubtedly, the agencies of Government would prefer that the Original tribes consented to Commonwealth law, allowing Government to dictate rights and privileges to the Original peoples, both now and in the future (you need only surrender your sovereignty once). And although Native Title is generally perceived by the broader Australian public as a legislative step toward ‘reconciliation’, it is clear the mechanism is designed to obtain the consent of the Original tribes, to have new rights granted by the Commonwealth in place of their existing sovereign rights.

As the recognized leader of the Ramindjeri, Karno Walker’s questionable treatment at the hands of Commonwealth Government agencies is starting to make sense.

In reality, the only way the Commonwealth can survive this constitutional crisis is to finally interpret and apply State, Commonwealth and United Nations law “in accordance with the principles of justice, democracy, and respect for Peoples’ rights, equality, non-discrimination, good governance, and good faith”. For the Commonwealth of Australia to maintain any constitutional or spiritual integrity, the lawful sovereignty of the Original tribal peoples must be honoured – in word, principle and deed.

The Final Word

Karno Walker is a highly recognised and respected tribal Elder and bearer of the tribal office of Senior Lawman. It is a sad irony that on the day of supposed “Aboriginal Recognition”, Mr. Walker was not recognized as a senior representatives of his tribe and, like generations of his ancestors, was instead subjected to the authoritarian discretion of Commonwealth agencies. Just as ironically, only 9 months before his arrest, Mr. Walker, along with Gunham Badi Jakamarra, was co-author of a paper organized by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, entitled “Strengthening Partnership Between States and Indigenous Peoples…” It seems their message once again fell on deaf ears.

So it seems only fitting that I offer the final word to those whose voice is systematically ignored – the Original tribal people.

Reflecting on Karno Walker’s experience, Ramindjeri Elder Unbulara had this to say:

I know that discrimination still exists in Australia but I really did not imagine that this blatant display of discrimination by the South Australian Police would have occurred in such a public place as the Parliament and in front of Parliament staff, the Black Rod and the Politician who had invited Karno to attend this event.

I was so saddened that this discrimination was allowed to take place in front of so many and by the people in our community we expect to be above that behaviour. We know all too well that in private places this discrimination exists, but now I worry that we as First Nation People cannot feel safe no matter where we are – even if the Police Force are in the vicinity.

Karno Walker is the Culture leader and teacher for the Ramindjeri people. He is also our spokesperson. Karno is a passionate man regarding our culture and rights as First Nation People. I am frightened for his safety more now that I see that even the Police force cannot be trusted to do the right thing. And the Courts fail to do their duty, bringing shame on their judicial system and more disgrace to Australian Society.

This article is dedicated to our brothers and sisters, the Original sovereign tribal people of Terra Australis. Thanks for reading.

About Andy Whiteley.

I’m just an average 40-something from Melbourne Australia who, like many people, “woke up” and realized everything isn’t what it seems. Since then, I’ve been blessed to be a part of Wake Up World and its amazing community of readers.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]