27th October 2015

Guest Writer for Wake Up World

One of the main themes of modern intellectual approaches has been to take away autonomy and freedom from human beings. From sociology to philosophy, from psychology to neuroscience, a common theme has been to try to show that our ‘free will’ is either limited or non-existent, and that we have much less control over our own lives as we like to believe.

In psychology, this was one of the central beliefs of behaviourism. You might feel as if you are a free human being, making your own decisions and choices, but in reality everything you do, or think or feel, is the result of environmental influences. Your behaviour is just the ‘output’ or response to the ‘input’ or stimuli which you have absorbed. Freudian psychology also emphasized a lack of free will. It suggested that the conscious self is just one small facet of the whole psyche – the tip of the iceberg – and that its activity is determined by the unconscious mind, including instinctive and biological drives.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

Existentialist philosophy and Humanistic psychology emphasised human autonomy, asserting that choice is one of the defining characteristics of human life, even if this isn’t necessarily a positive phenomenon. According to Kierkegaard, the sheer extent of our freedom may induce a state of disorientation and dread, and make our choices ‘in fear and trembling.’ Similarly, Sartre believed that the freedom to choose courses of action without knowing their consequences contributed to life’s absurdity. (In his famous phrase we are ‘condemned to be free.’) In reaction to Behaviourism and Freudian psychology, humanistic psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers asserted that human behaviour is not necessarily determined by our past and present experiences, since we always have the capacity to make choices based on our own assessments of situations.

However, in sociology, there was a movement towards the denial of autonomy. Theorists argued that your sense of self is a ‘social construction’, and that it is impossible for identity – and by extension, free will – to exist outside a nexus of social influences that determine our lives. Linguistic theorists argued that our reality is created by language, and that we cannot see the world outside the framework of the semantic and grammatical structures we have absorbed from our parents and our cultures.

Gene Theory and Neuroscience

However, modern gene theory and neuroscience deny autonomy and free will in a much more direct way. According to gene theorists, we exist as ‘carriers’ for our genes, to enable them to survive and replicate themselves. Everything we do is determined by – or done on behalf of – our genes. Our behaviour is either the result of ‘leftover’ traits which were developed by our ancestors because they provided some survival advantage, or the result of our desire to increase our reproductive success. For example, according to Steven Pinker, the reason why we find lush countryside landscapes beautiful is because to us that represented a plentiful supply of resources to foster survival. The reason why some of us feel ‘driven’ to gain success in fields like politics and creativity is because success makes us more attractive to the opposite sex, and so increases our reproductive possibilities.

In terms of neuroscience, brain activity – or neuronal networks and brain chemicals – play a similar causal role to genes. Your moods, your desires and your behaviour are determined by the levels of various brain chemicals (such as serotonin or dopamine) or by ‘neuronal networks’ which may predispose you to certain impulses or traits. If you feel depressed, it’s because of a low level of serotonin. If you are a psychopathic, it’s because areas of your ventromedial prefrontal cortex are less active than normal. If you are a born again Christian, it’s because you have a smaller than normal hippocampus. (Believe it or not, the latter two statements have actually been put forward as theories.)

These genetic and neuroscientific interpretations of behaviour are both what might be called ‘can’t help’ approaches. We ‘can’t help’ being depressive, psychopathic, religious, racist, polygamous (if you are a male) and so forth, because our genes have programmed us to be like this, or because we are biologically burdened with the brain chemistry associated with such behaviour.

Harnessing Free Will

What is the root of these assaults on our autonomy? Why do intellectuals and scientists feel such a strong impulse to show us that we are powerless, completely in thrall to forces beyond our own control? Perhaps it’s an unconscious desire to abdicate responsibility. Perhaps the modern world has become so complex and stressful that scientists and philosophers feel an impulse to admit defeat and retreat from responsibility, to pretend that we have no control over the chaos.

I wouldn’t go this far myself, but a conspiracy theorist might argue (and perhaps some already have) that this ‘autonomy-denial’ is a form of oppression, an attempt by the intellectual elite to keep us down, convincing us that we are powerless so that we won’t challenge their authority. Or more rationally, it may be related to the nihilistic desire to prove that there is no ‘self.’ Free will is, of course, one of the strongest features of ‘the self.’ If you believe that there is ‘no one there’ inside our mental space, that our sense of self is just an illusion or the product of neurological processes, then you have to believe that free will is an illusion too.

But no matter their motivation, one is tempted to reply to these assaults on free will in the same way that the 18th century author Doctor Johnson responded to the philosophical claim that matter did not really exist. ‘I refute it thus!’ he shouted, as he kicked a stone. Doctor Johnson could have used the same method to illustrate the capacity for free will. It’s difficult for any philosopher or scientist to argue that we don’t have free will, when our everyday experience is that there are always a variety of possible choices of action in front of us – like a pack of cards spread out for us to pick from – and we feel we have the freedom to choose any of them, and to change our minds at any point. After all, whenever you read a book or listen to a lecture claiming that there is no such thing as free will, you’re always free to close the book, or to throw a tomato at the lecturer.

One of the problems here is that scientists and philosophers often tend towards absolutism. Gene theorists often argue that behaviour is completely determined by our genes, neuroscientists argue that behaviour is completely determined by brain activity, social constructionists and behaviourists argue that social and environmental forces completely determine our behaviour, and so forth. In my view, it’s much more sensible to be democratic than absolutist. It’s likely that all of these factors have some influence on our behaviour. They all affect us to some degree, but none of them are completely dominant. And free will is itself one of these factors, part of this chaotic coalition of different influences. The conscious self is certainly is not an authoritarian dictator, but it isn’t a slave either. No matter what social and environmental forces have influenced me, no matter what genes or brain structure I’ve inherited from my parents, I have some degree of free will too, and I can decide whether to kick the stone or not.

Increasing Our Free Will and Autonomy

I would argue that one of the most important tasks of our lives is to develop more free will and autonomy. One of the primary ways in which we can develop positively and begin to live more meaningfully is to transcend the influence of our environment, and become more oriented towards who we authentically are. As Humanistic Psychology suggests, there is a part of us with innate potentials and characteristics which is independent of external factors – even if that part of us may be so obscured that we can barely see it. But our task should be to allow that part of us to express itself more fully, which often means overriding environmental and social influences.

This even applies to genes and brain chemistry too. They may predispose us to certain types of behaviour, but we can use our autonomy to resist those influences, to control and even re-mould our behaviour. It’s by no means easy, but we can overcome our programming. We don’t have to blindly follow the environmental, genetic and neurological instructions we were born with. We can increase the quotient of free will and autonomy we were born with, to the extent that it becomes more powerful than genetics, neurology or the environment. (Strangely, despite his rigid genetic determinism, Richard Dawkins agrees with this, stating that human beings are the only living beings who have the power to ignore the dictates of their genes).

And interestingly, neuroscientific ideas about the limitations of free will are contradicted by neuroscience itself. Recent research has shown that, rather than being fixed, our brain structure is very flexible, and continually changing. The brain is not ‘hard-wired’ but ‘soft-wired’. The relatively new field of neuroplasticity shows that practicing certain habits or behaviours brings real physical changes to the part of the brain associated with that activity. For example, if you decide to learn to play the piano, you will develop more neural connections (and perhaps even more brain cells themselves, through the process of neurogenesis) in the parts of the brain associated with motor activity and musical ability. If you meditate regularly for years, you will develop more ‘gray matter’ in the areas associated with attention, concentration and compassion. So in that sense, rather than being completely controlled by our brains, we have control over them.

Similarly, the rigid determinism of gene theory is contradicted by recent findings in relation to genetics. The field of epigeneitics shows that the genetic structures we inherit from our parents don’t remain fixed throughout our lives either. Our genetic structures are altered by the life experiences we undergo, so that the genes we pass on to our children will be different to those we inherited. For example, experiments have shown that when mice are trained to develop an aversion to a particular smell, this aversion will be passed down to their offspring, who become 200 times more sensitive to the smell than other mice. This new behaviour is reflected in changes to the genes and brain structure of the mice. And in human beings, studies of twins show that, when twins are exposed to very different environments and life experiences, in their later life they show striking differences in their DNA. In a study of the descendants of a population in Sweden which underwent famine in the 19th century, it was found that the men had a stronger than normal resistance to cardiovascular disease, while if women were descended from grandmothers who had been exposed to the famine while in the womb, they had a shorter than average life span.

One extension of this would be to actively take responsibility for our genes, knowing that the health and well-being of our descendants depends on them. We could make a conscious effort to live positively, to be free of trauma and stress and undergo as many positive and rich experiences as possible, in order to ensure that the genetic inheritance we pass on to our children is as ideal as possible. In this way, it could be said that we have the capacity to control our genes, rather than them just controlling us.

Perhaps there are some people – many, even – who do largely seem to be the products of their environments, and of their biological inheritance. But I would argue that whatever the term ‘greatness’ means, it is usually manifested by people who have exercised their autonomy to a large degree, and largely freed themselves from external influences. These are usually people of strong will power, and have used this to harness and hone their natural abilities, until they developed a high level of skill and expertise. They have used their autonomy and self-discipline to expand themselves, to actualise their innate potential and become more than the sum of their environmental influences.

In a sense, this is only an extension of what every human being ideally does as they move from childhood to adulthood: to develop more self-control and autonomy. With the help of our parents, as we move through childhood, we begin to control our impulses and desires. We learn that we can’t have everything exactly when we want it, and so learn to delay gratification, developing some self-control. As we begin to need less care and attention from our parents, we exercise more autonomy. We learn to make more decisions for ourselves and to follow our own intrinsic interests and goals. In this sense, human development is a process of becoming less bound by biological and environmental influences – a process of gaining more free will and autonomy. And ideally, this process should continue throughout our lives.

In Eastern traditions, spiritual development can be seen as a process of gaining increased freedom and autonomy too. Many Eastern spiritual traditions such as Buddhism and Yoga place a great emphasis on self-discipline and self-control – control of one’s own behaviour, so that we no longer cause harm to others; control of our desires, so that we no longer lust after physical pleasures; control of our thoughts, so that we can quieten the mind through meditation, and so on. In some traditions, spiritual development is seen as a process of ‘taming’ the body and mind, which is, of course, only possible through intense self-discipline and self-control. Although it can sometimes occur suddenly and spontaneously, the deep serenity and intensified awareness of spiritual awakening is usually the culmination of a long process of increasing our innate ‘quotient’ of personal freedom and autonomy to the point where this becomes dominant amongst all of other influences. When ‘awakened’ people are referred to as ‘masters’, this could easily refer to them being masters of themselves.

In Western philosophy, Nietzsche meant something similar with the concept of ‘self-overcoming.’ Nietszche spoke disparagingly of the ‘Ultimate Man,’ the person who is completely satisfied with himself as he is, and strives only to make his life as comfortable and enjoyable as possible. But in reality, says Nietzsche, human nature is not fixed or finished. Human beings are part of a dynamic evolutionary process, not a goal but a bridge: ‘a rope fastened between animal and Superman.’ The potential Superman is the human being who is not self-satisfied, who has the urge to ‘overcome himself.’ For him, life is an attempt at ‘going across’ the gulf between animal and superman.

So we all possess a degree of freedom, and freedom is not a static quality. We all have the capacity to extend the degree of freedom we’re bequeathed with, to become less dominated by our genes, our brain chemistry, and the environment or society which we’re born into. We are potentially much more powerful than we have been led to believe – even to the extent of controlling or altering the forces which are supposed to completely control us. As stated above, this applies to our brain structures, our genetic inheritance – and also, of course, to our environment and our society. And to a large extent, our well-being, our achievements and sense of meaning in life depend on this. The more you exercise and increase your freedom, the more meaningful and fulfilling your life will be.

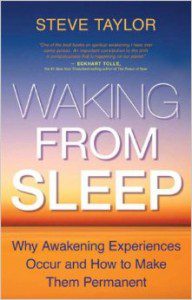

Waking From Sleep: Why Awakening Experiences Occur and How to Make Them Permanent

A book by author Steve Taylor.

How much of your waking time are you fully awake? On the other hand, how often do you stumble through the day on autopilot, half-asleep and out of contact with yourself, instead of feeling connected and alive?

How much of your waking time are you fully awake? On the other hand, how often do you stumble through the day on autopilot, half-asleep and out of contact with yourself, instead of feeling connected and alive?

In this astounding book, author Steve Taylor suggests that our normal consciousness is really a kind of “sleep” from which we sometimes “wake up” into a more intense and complete reality. He provides what is perhaps the first-ever clear explanation of higher states of consciousness, or “awakening experiences”.

Waking From Sleep delves into: the methods we human beings have used throughout history to induce awakening experiences, including meditation, sex, sports, psychedelic drugs, and sleep deprivation; how higher states of consciousness were normal and natural to some of the world’s peoples (and still are, in some cases); and how we can make “wakefulness” our normal state again. By fully explaining awakening experiences, the author makes them much more accessible, which may lead to a revolution in our psychological development as human beings!

‘Waking From Sleep’ is available here on Amazon.

Previous articles by Steve Taylor:

- Harmony of Being – Returning to Our True Nature

- Touching the Earth Again

- Transcending Time in Egoless States of Consciousness

- Transcendent Sexuality — How Sex Can Generate Higher States of Consciousness

- The Power Of Silence

- Happiness Comes from Giving and Helping, Not Buying and Having

- Empathy – The Power of Connection

- Transcending Human Madness

- If Women Ruled the World – Is a Matriarchal Society the Solution?

About the author:

Steve Taylor holds a Ph.D in Transpersonal Psychology and is a senior lecturer in Psychology at Leeds Metropolitan University, UK. For the last three years Steve has been included in Mind, Body, Spirit magazine’s list of the ‘100 most spiritually influential living people’ (coming in at #31 in 2014).

Steve Taylor holds a Ph.D in Transpersonal Psychology and is a senior lecturer in Psychology at Leeds Metropolitan University, UK. For the last three years Steve has been included in Mind, Body, Spirit magazine’s list of the ‘100 most spiritually influential living people’ (coming in at #31 in 2014).

Steve is also the author of Back to Sanity: Healing the Madness of Our Minds and The Fall: The Insanity of the Ego in Human History and the Dawning of A New Era. His books have been published in 16 languages and his research has appeared in The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, The Journal of Consciousness Studies, The Transpersonal Psychology Review, The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, as well as the popular media in the UK, including on BBC World TV, The Guardian, and The Independent.

Connect with Steve at StevenMTaylor.com and Facebook.com/SteveTaylorAuthor.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]