By Katrin Geist

Contributing writer for Wake Up World

Shit Happens, Easily – Or Does It?

It may come as a surprise: your intestines play a vital role in your good health. If something’s amiss there, you’ll know it. Sometimes malfunction expresses as mere inconvenience, other times it points to severe imbalance or illness. Our gut is central to our wellbeing and may well be the most underrated and underappreciated organ of our body.

Let’s change that by understanding its function and service to us. Every day, your gut serves you. No matter what you offer it. Every day it turns muffins, coffee, pasta, vegetables, cake, bread, fast food and everything else into molecules we then use to generate energy and to build our own structure.

How Digestion Works

Briefly, we use three major food groups to build and run our body: carbohydrates (simple & complex sugars), fats and proteins. In order to use them as fuel, however, the body must first break down things we ingest. It’s like taking apart a Lego castle to build a ship instead. Both share the fundamental building blocks but yield different shapes according to function. A steak doesn’t remain a steak for very long, as our organism cannot use it in that form. But individual building blocks – proteins (amino acids) – may serve to build our own structure. Same for reuse of sugars and fats.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110028″]

The Mouth

So what happens when we eat something? Digestion begins in the mouth. Or perhaps with the eyes? When you look at delicious food, your stomach starts producing hydrochloric acid in anticipation of what’s coming. You produce saliva, too. Your salivary glands create between 1-1.5 litres of saliva daily by filtering blood. Among others and besides water, saliva contains electrolytes (e.g. potassium, bicarbonate), the pain killer opiorphin, and antibacterial compounds. Entering food becomes insalivated and mechanically broken down by teeth, while oral bacteria already begin digesting food particles. Upon swallowing, the food-saliva mix travels down the esophagus into the stomach to meet a highly acidic environment.

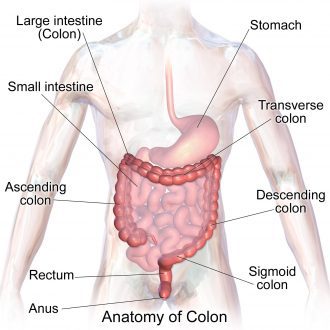

Figure 1: Gastrointestinal (GI) tract: mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine (colon), rectum, anus.

The Stomach

Mechanical break down of food continues here. The stomach churns food by muscular contractions (peristalsis). It also begins cleaving proteins into polypeptides (shorter chains of amino acids). The enzymes (type of protein) for this task require an acidic pH, provided by hydrochloric acid. Stomach resident time after a meal is about two hours, before the predigested food mix passes on to the small intestine. That said, foods vary in their passage time. While “white foods” (e.g. white bread, noodles, rice), built of more simple sugars, pass on relatively quickly, the stomach retains proteins and fats for longer. It may take six hours for that steak to pass through the stomach.

The Small Intestine

As food enters from the stomach, chemical digestion begins in earnest. With the aid of bile from the gall bladder, pancreatic juice, and peristaltic movement, proteins, fats and sugars break down into their fundamental building blocks: proteins to amino acids, complex sugars to simple ones (e.g. glucose), and fats into fatty acids and glycerol. Our steak takes about five hours to pass through and undergo these major changes.

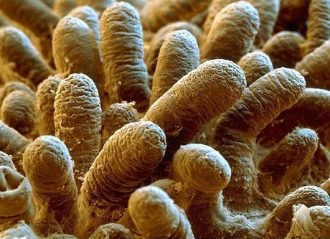

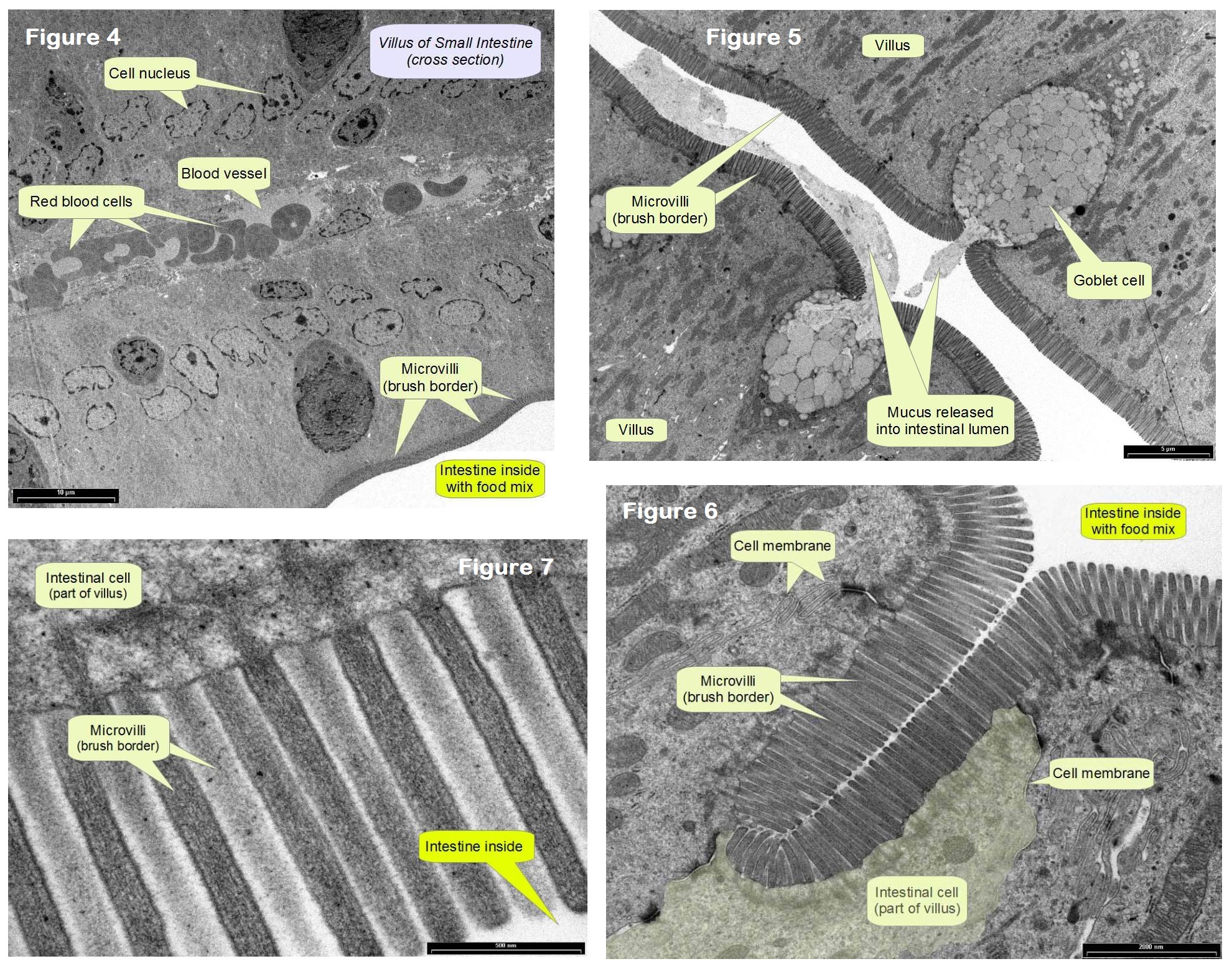

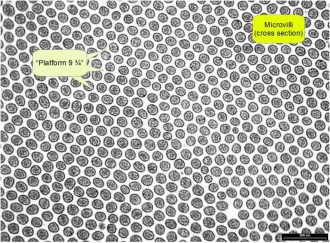

The intestine’s secret to success lies in its tremendous surface area: >100x bigger than our skin surface. How does it do that? It’s a master of folding and packaging (Fig. 2). The inner intestinal lining consists of gazillions of folded protrusions (Fig. 2, 3) called villi. Villi in turn possess finger-like projections on their surface (microvilli) to increase the surface area even more. Viewed in cross section this microvilli field is also called the brush border, for obvious reasons (Fig. 4-8).

Figure 8: Microvilli field in cross section (rat). “Platform 9 ¾” is between microvilli, and ultimately the villi cell membrane itself, where metabolites eventually cross through into intestinal cells.

As parts of the villi, goblet cells secrete mucus into the intestinal lumen (inner space) where it forms a 200 µm thick layer that lubricates and protects the inner intestinal lining (endothelial cells), aiding with peristaltic passage of the food mix (Fig. 5). Together with digestive juices which help metabolize nutrients and minerals, while being pushed along, the food mix further and further breaks up into its components, until particles are small enough to pass through endothelial cell membranes. As Giulia Enders (2015) put it so picturesquely, broken down food particles disappear from the intestinal lumen like Harry Potter on platform 9¾ – they cross into cells of the intestinal lining between villi and microvilli (Fig. 6-8), before passing into the blood stream (Fig. 4) for distribution to places of demand.

If one would stretch out all villi and microvilli, our intestinal length would amount to an astounding ~ 7 km (instead of the actual c. 7 m)! One square millimeter of intestinal surface extends about 30 villi (Fig. 2) into the passing food mix, extracting nutrients and minerals. Without the increased surface area, our digestion (and life) would be a sorry affair. Food would pass through too quickly, allowing too little time for break down, absorption, and use. We would be lousy digestors, requiring multitudes of normal food intake to extract enough energy to live. We’d probably eat all day. Digesting over a great surface area allows for efficient use of ingested food stuffs. A piece of apple contains billions of molecules. To absorb all those (and benefit from eating an apple), it takes a large surface area. Thankfully, our villi and microvilli achieve that beautifully and effectively.

Absorbed nutrients (sugars and protein parts) then travel in the blood stream to the liver which screens for toxic substances and filters blood coming from the intestines before releasing it into the main circulatory system. Fats take a different route. Since they’re not water soluble, fats would clog up small blood vessels (Fig. 4). Instead, the intestine passes fat molecules to the lymphatic system which, via the Ductus thoracicus (major lymph vessel), empties it directly into the heart (no prior liver screening here). The lymphatic system has no distribution engine like the blood circulation. Instead, muscle movement and gravity propel lymph fluids.

So much for the goodies we extract from food to fuel our life processes – what about the rest though?

The Large Intestine (Colon)

As the food mix – now not very reminiscent of the meal you ate – advances into the colon, things slowly turn into the beloved expression we commonly hear people exclaim the world over – ssshit! Only the last meter of colon deals with fecal matter, however. The rest absorbs nutrients and water from the food-digestive juice mix, pushing it along to the last meter, where the process culminates in resorbing water, compressing indigestible food matter, forming stool, and ultimately expelling it altogether.

Anything that couldn’t be broken down so far now gets a chance at the hand of a gazillion resident colon bacteria. Cellulose, for example. We lack the enzyme to break it down, but bacteria do not.

You’re Bugged

Time for truth: you are not alone. Not ever. Rather, you’re a formidable habitat – a superb living space for small things loving warm, moist places. Our innards host up to 1000 different bacteria species (Foster & McVey Neufeld 2013). Minorities also occur: viruses, fungi, yeasts, and other unicellular organisms. E.coli only comprise c. 1% of our gut microbiota. Bacterial density increases as we progress along the GI tract, with greatest abundance in the colon. One gram feces contains more microbes than all the people living on this planet combined (>7 billion). Your very own c. 100 billion gut tenants contribute up to 2 kg of your body weight. Alas, taking antibiotics would be a dreadful option to lose those 2 kg. This is gooood weight. Under healthy circumstances, at least.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110030″]

So what’s with these bugs? Feeling outnumbered? You are. By nine to one. About 90% of the human superorganism belong to microbes, and human cells account for c. 10%. Due to the size difference, we don’t notice though. The colonizing process begins right at birth, where a baby carries only few maternal microbes. But this changes quickly and by the age of three, as far as gut microbiota go, you’re grown up (Derrien & van Hylkama Vlieg 2015) and posses your very own unique microbial blend, which continues to adjust throughout your life (Jeffery & O’Toole 2013), depending on culture, diet, stress levels, medication, and other factors (Maukonen & Saarela 2013, Foster & McVey Neufeld 2013).

Thing is, if you were sterile, life would be very difficult. Bacteria possess a number of abilities that we lack. In exchange for room and board, they share their talents with us. Compared to our approximately 25.000 genes, our gut tenant’s combined genes amount to >5 million. Many of these encode biosynthetic enzymes or those which break down molecules, such as proteases (protein cleaving) and glycosidases (sugar cleaving). This greatly expands our biochemical and metabolic repertoire (Sommer & Bäckhed 2013). Gut bacteria help break down food even more than we could on our own. They also generate vitamins and energy our colon can use(Jeffery & O’Toole 2013), degrade toxins (think mouldy bread) or medications, define our blood type, and train our immune system. Since most of our digestion already occurred in the small intestine, what colonic microbiota break down and release is like a bonus. They aid us in extracting the maximum of resources from our diet, influencing how well we digest specific foods (think allergies), how well we process medication, how vulnerable we are to pathogens, and even how we feel in general. People dealing with stress-related disorders (anxiety, depression), atherosclerosis, or obesity, for instance, carry a distinctly different gut flora than people who are well (Luna & Foster 2015, Sommer & Bäckhed 2013). Whether this is causative or consequential of respective conditions remains unclear, however (Bäckhed et al. 2012).

It is also well established that a healthy, intact gut microbial community protects its host against infection by gastrointestinal pathogens, a phenomenon known as colonization resistance (Vogt et al. 2015). And it doesn’t stop there. New research shows that bacteria also influence processes initially thought to concern only the host alone: organ development, bone mass, cell proliferation, obesity, and even mood and behavior (Luna & Foster 2015, Sommer & Bäckhed 2013).

The Gut: The Immune System Boot Camp

Eighty percent of our immune system sit in the gut. It’s the perfect boot camp to teach what belongs and what doesn’t. Exposure to the real thing works best for learning. The gut provides an ideal environment: while its mucus lining (Fig. 5) protects us from bacterial invasion and damage, immune system cells can learn what different microbes look like, so as to recognize them again later, while patrolling other tissues where pathogens could wreak havoc. Since the gut harbors so many different kinds of microbes, the immune system receives excellent education on many kinds of possible invaders. It learns to recognize them for future reference, building its memory bank. Without this training ground, we would be insufficiently equipped to deal with potentially invasive organisms.

Since gut microbiota play such a crucial role for the entire organism, develop with it, consist of cells, communicate, and exhibit a metabolic capacity equal to the liver, some scientists consider our intestinal tenants as an additional organ (Sommer & Bäckhed 2013, Xu & Gordon 2003).

So there’s no reason to dislike your wee companions. Some people even buy them! It’s called yogurt, sauerkraut, or probiotics (see below).

Using a Toilet Right

Who would have thought there is such a thing as the right position when it comes to our daily deed, but there is. Shovel-equipped outdoor lovers know this. The natural squat position looks and the posture we commonly assume on the toilet seat are shown in Fig. 9.

Anatomically, the natural squat straightens the colon for easy release. The sitting pose in Fig. 9 does not, however. You can easily correct this by moving your heels back and up and leaning forward a bit. Alternatively, you can get a foot bench to help elevate your feet and assume a more natural squat position. To encourage your colon into releasing its load, you can also move between leaning forward and backward a few times, like a lever. It works. Nobody sees you do it, so might as well dare try this little exercise, aye? 🙂

For more information, please see: Potty Talk: Why You Should Squat for Better Digestive Health

What’s The Normal Elimination Frequency?

It takes about one day to digest a meal before it knocks on the exit for release. However, there seems no hard and fast rule for this. People differ widely in their frequencies, including gender and cultural backgrounds. While some produce three or four piles per day, others evacuate once, and still others eliminate three times per week. Your normal frequency may or may not concur with this medical statistic, which views three times a week as still healthy. It seems too infrequent to me, subjectively. Ayurveda views one bowel movement per day as ideal, whereas still others hold that one should eliminate twice or more daily (Group 2010). I think as long as the texture is a normal type 3 or 4 and you feel fine, you probably are. Quite literally, listening to your gut feeling may be a good idea to get your answer.

Signs of a Healthy Gut Turned Sour

Stool Properties

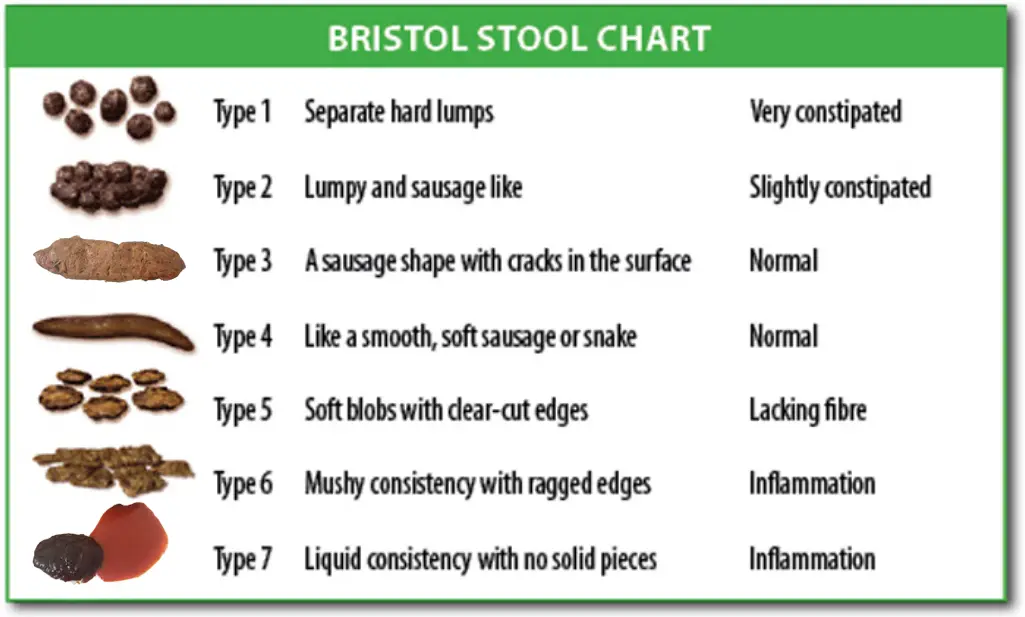

We hardly refer to the real thing when discussing “shit” in public or with friends. Yet understanding what’s in the toilet bowl is helpful, especially when struggling with digestion. The color, texture, shape, size, and form of your stool reflect your diet, fluid intake, possible illness, lifestyle, and medications. The Bristol stool chart is an easy tool to see where you reside in the spectrum of possible outcomes. The nature of your stool depends on its resident time in the colon, the kinds of food you eat and any disease afflicting the body. They say success leaves clues. Shit does, too (Fig. 10).

Above chart is self-explanatory, and no doubt you will have come across most of these at some point in your life. Type 3 and 4 represent a healthy texture with more or less optimal water content. Deviations should be temporary. If any other type is normal for you, consider seeking advice on how to revert back to type 3 and 4. Stool texture hints at gut resident time: for type 1, this may be up to 100 hours (constipation). For type 7, it may only take 10 hours (diarrhea).

Pile Anatomy

Three quarters of your pile consists of water. While the digestion process reabsorbs most if it, what’s left is necessary for easy passage out the rectum. One third of solid waste stems from worn out bacteria. Another third comes from indigestible plant fiber. The more fruit and vegetables you eat, the larger your pile, sometimes exceeding the usual volume (100 – 200 g/ day) by up to five times (500 g/ day). The last third includes toxins, remnants of medication, food colorings, and other unwanted metabolic waste products.

Color

Stool color may indicate health problems. The healthy color is brown or golden, just like urine usually assumes a tone of yellow (a very pale yellow color, next to transparent, indicates a well hydrated state). Pigments of disintegrating blood cells undergo a change from red to green to yellow (a sequence also visible in progressing bruises). Urine takes its yellow color from this, and gut bacteria, upon receiving worn out blood cell parts from the liver, add brown to give stool its familiar color.

- Yellow stool hints at malfunctioning gut bacteria, possibly caused by diarrhea or antibiotics.

- White stool may either result from a mucus coating or possible interference with bile formulation. If it’s solid white throughout, a specialist visit is in order.

- Green stools often reflect recent consumption of green plants (e.g. a salad) and usually pose no reason for concern, unless green color is your ongoing normal, without relating to a recent green meal. Then it might pay to take a further look to exclude any gut problems. Other causes of green stool include consuming sugar in excess, supplements (e.g. chlorella), food passing through too quickly (e.g. allergies, stomach virus), or performing a liver/ gallbladder cleanse (purged toxins).

- Grey stool color may indicate a disturbed connection between liver and intestine, which prevents old blood cells/pigments entering the intestine, and thus no brown coloring ensues from lack of substrate (for gut bacteria that add brown color). A healthcare practitioner visit is recommended here.

- Red or black color comes from fresh or coagulated blood. Sometimes, since the colon is such a densely serviced blood vessel area, tiny vessels can break and release a bit of fresh (brightly red) blood. No worries. Dark red or black stool should definitely be checked out by a healthcare professional, however – unless you ate beetroot the day before.

Shape

Healthy stool looks sausage like, with a peanut butter texture (type 3 & 4). Deviations should be temporary. If your stool looks ribbon-like, it could hint at polyp development in the colon. Fecal matter must bypass these, which may change stool shape (Polyps are wart like growths on the intestinal lining; people are often asymptomatic; constipation, diarrhea and blood in the stool may be signs of polyp presence). Ribbon-like, thin stool may also indicate presence of cancer or scar tissue – see someone qualified to determine the cause.

Foul Smell

If your pile comes with a foul smelling, putrid odor which lurks in the toilet for more than three minutes, your body asks for attention. A colon or ‘green body cleanse’ (see below) may help. The odor may arise from eating too much animal protein or an imbalance of gut microbiota.

Mucus Cover

Seeing mucus on stool must not usually alarm you. It’s part of normal gut biology. That said, people can produce excess mucus, and it may indicate an unhappy gut or a more serious problem if it persists. If present for more than a few weeks or accompanied by a foul smell or bleeding, see a healthcare professional. Mucus covered stools could indicate ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, infection, or bowel obstruction (Group 2010).

Constipation

I think most everyone has experienced straining to pass dry, hard stool. It’s unpleasant enough occasionally, let alone regularly. The good news is you really can do something about this and make it a thing of the past, or at least a rarity in your life (see below). Other symptoms of constipation may also include increased “bowel music”, gas, bloating, fatigue, bad breath, or skin blemishes.

Impacted Waste

Is the accumulation of compacted, hard fecal matter adhering to the intestinal walls. This crusty buildup, which remains in place during normal bowel movements, may result from years of poor lifestyle choices (e.g. diet, toxin exposure, no sports/ sedentary habit). Dr. Group of Global Healing Center estimates the average American to carry around several pounds of impacted waste by the time they reach age 30. He also says that obstructed bowel activity may contribute to obesity. Given the staggering statistic that nearly 80 million Americans are obese (CDC 2014) and millions also battle with constipation/ intestinal problems (CDC 2014), perhaps the solution lies in their gut? Some studies point out a decreased diversity of gut microbiota in obese people and those with inflammatory bowel diseases (Doré & Blottière 2015, Bäckhed et al. 2012) – cause or consequence?

Frequent Gas or Bloating

Bloating and gas usually relate to what and how we eat. Rich, fatty foods may cause it, as does not chewing well enough. The less we chew, the more work we leave for stomach and intestines to break down food stuffs. Gas develops as a result of microbial activity and from swallowing air, e.g. when using a straw, guzzling fizzy drinks, or chewing gum.

Passing gas, bloating, and burping form a natural part of digestion. However, if gas does not get released, it can build up and cause bloating and abdominal discomfort. Usually, bouts of excessive bloating and gas resolve on their own. Sometimes, gas indicates a digestive disorder such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome or lactose intolerance.

Ways to Restore and Keep a Healthy Gut

This can be an involved topic, and I’ll only introduce some solutions here, primarily intended for people with occasional issues like constipation or gas, and for those wanting to keep their gut healthy and prevent disease. If you contend with serious, prolonged trouble, working with a therapist sounds a good idea. While I’m all for the do it yourself at home approach, sometimes getting expert guidance just pays. Your gut is central to your wellbeing. It affects all other areas of your body. If you sort that aspect, others (as knock-on effects) may fall away naturally. You’re then in a position to take back the reins and look after a restored GI tract and your good health over all.

No Shit – Now What?!

One of the most common bowel complaints is constipation. Every fifth US American suffers from a form of digestive impairment (Group 2010). These ayurvedic methods may bring relief:

- Drink a glass of lukewarm water with 1-2 teaspoons of honey in it 3-4 times a day, or

- Mix powdered dried ginger root, long pepper, black pepper, and black salt in equal quantities. Have 1 teaspoon of this mixture at bedtime with lukewarm water and 2 to 3 teaspoons of psyllium (isabghul) husk, or

- Mix powdered celery seeds, cumin seeds, and asafoetida in equal quantities and have ½ teaspoon 15 minutes before meals twice a day (Chakrapani Ayurveda 2015).

I also find drinking a glass of lemon water first thing in the morning helpful. Grated apple and carrot also empty the colon rather well. A prominent cause of constipation is a sedentary lifestyle – so move! Regularly. Keeping hydrated serves all cells and helps the colon form perfect stool (type 3 or 4) – so, drink enough water! Consuming Oxy-Powder (see below) also works well.

Generally, regular exercise (3x or more per week), eating more dietary fiber (fruit & vegetables) and drinking enough water should prevent constipation and keep your colon happy.

Fasting and Detox

While no immediate solution, a fast nicely resets your body and gives it a break from expending lots of energy on digestion. I’ve written on it extensively here. A detoxification regimen can work wonders for people. I adhere to a juice fast twice a year, for example, and also perform the occasional liver and gallbladder cleanse. Dr. Group’s “Green Body Cleanse” teaches how to keep yourself and your living environment less toxic. He believes that illness basically comes from a toxic, compromised colon and shows ways to restore the GI tract and maintain its health thereafter. This is a worthwhile read for anyone dealing with gut problems and/ or seeking to maintain a healthy digestive system. Dr. Group also has a book titled “Complete Colon Cleanse: The At-Home Detox Program to Restore Good Health, Boost Vitality, and Ensure Longevity”, which fits our subject rather well. Since I just discovered it, I’m not sure of the overlap between both books, however “The Green Body Cleanse” gives a good overview and practical guidance on how to decrease the body’s toxic load from all kinds of sources, e.g. diet and environments, and on how regular colon cleansing benefits the entire organism.

Cleansing

In addition to liver, gallbladder, and kidneys, one can also perform a colon cleanse. Indeed, this should come first. It involves gently irrigating the colon with warm water and flushing out feces. While you can do an enema at home, I would opt for a professional setup and visit a hydrotherapy center in the beginning. I prefer one time use equipment over sterilizing and reusing spatulas – a personal preference everyone can decide on. It may be a question worth asking before making your appointment.

While I’m not aware of a facility in Dunedin, I can recommend Colonic Health Centre in Auckland. They use disposable equipment, provide a professional, hygienic setup, are very friendly and instruct you well in the process. Privacy and dignity are ensured – there’s no reason to not go and try this. 🙂

If you do not have access to a center and dislike enemas, you can try Oxy-Powder, a formulation by Dr. Group’s Global Healing Center that relieves the colon of fecal matter, including impacted waste. It simply delivers oxygen to the gut which then “bubbles away” and detaches fecal matter from the colon wall. It definitely works… =) It also increases the number of bowel movements per day, so using a weekend as a first try might be a good idea. I apply Oxy-Powder mostly while fasting, to clean the intestinal lining. Together with drinking plenty of pure water it frees the gut quite effectively. People also report great results for bloating and waste compaction, symptoms associated with constipation, and apparently there were successful clinical trials regarding Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Group 2010).

Diet

What we eat directly influences how we feel. Funny enough, we often times fail to recognize this connection. Our gut microbiota do not, however. Research found distinct differences of microbiota diversity and composition in people adhering to vegan vs vegetarian vs protein based diets (Maukonen & Saarela 2013, David et al. 2013). The nutrient composition of ingested foods determines which microbes colonize the gut and flourish and which ones don’t (Jeffery & O’Toole 2013). Gut microbiota can rapidly respond to dietary changes (David et al. 2013) while also maintaining a healthy, stable, and highly individual community composition long-term (Derrien & van Hylkama Vlieg 2015, Doré & Blottière 2015). Given the way human eating habits have changed over the last 100 years, with the proportion of processed foods ever increasing, one can easily imagine the likely dramatic changes this triggered within our guts.

“It may be that our consumption of processed foods, widespread use of antibiotics and disinfectants and our modern lifestyle may have forever altered our ancient gut microbiome. We may never be able to identify or restore our microbiomes to their ancestral state, but dietary modulation to manipulate specific gut microbial species or groups of species may offer new therapeutic approaches to conditions that are prevalent in modern society, such as functional gastrointestinal disorders, obesity, and maybe even age-related under-nutrition. Our intestinal microbial community can affect the rate of deposition and utilization of fat, insulin resistance and diabetes and our inflammation state, as well as our general health and wellbeing” (Jeffery & O’Toole 2013).

If higher microbial diversity indicates good health, as seems the case, then a plant based (high-diversity fiber) diet is favorable for keeping a happy, healthy gut. It promotes beneficial bacteria and suppresses pro-inflammatory ones (Doré & Blottière 2015). Apart from that, eating organic wholefoods and minimizing processed food intake simply makes sense, on all accounts. If we offer the body something it does not recognize, naturally, its processing is more difficult. Toxic accumulations then may cause health problems downstream.

Increasing the fiber portion of your meal helps form bulk and allows waste to pass along more smoothly and quickly. Regular consumption of foods known to stimulate digestive enzymes also helps: brown rice, garlic, ginger, onions, radish, as does eating fermented foods like yogurt, sauerkraut, or pickles.

Things good to reduce include coffee, refined foods, and laxatives. Some medications also affect the digestive tract – ask your doctor if it’s possible to reduce/ change medications, for example in case of recurring constipation where a formulation is known as a contributing factor.

Hardly anyone chews food enough. Ideally, it turns to pulp in your mouth before swallowing and passing it on to the stomach. Rule of thumb is 25 chews per mouthful.

Lastly, avoid drinking water with meals, as this slows down digestion. Added liquid will dilute the digestive juice and result in food lingering longer than necessary. If you must drink with a meal, keep the volume as small as possible.

Supplements

Probiotics: Probiotics are live micro-organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host. Most currently used probiotics employ the genera Bifidobacterium andLactobacillus, and some showed clinical benefits for antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Necrotizing Enterocolitis, pouchitis, ulcerative colitis, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Bäckhed et al. 2012). Dr. Group (2010) also reports success with easing gastrointestinal symptoms, food sensitivities, and digestive function.

Given that microbiota can influence behavior, in particular stress-related ones such as anxiety and depression (Luna & Foster 2015), the news that probiotics administered to mice reversed their stress-induced anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors (David et al. 2013) is hopeful.

During recent years, probiotics increasingly feature in non-dairy foods such as fruit and berry juices and cereals. In good quality products, the daily dose should contain approximately 109 colony-forming units/d(Maukonen & Saarela 2013).

The mechanisms underlying the positive effects of probiotics remain incompletely understood, especially as they relate to modifying the gut microbiota and associated microbial functions (Bäckhed et al. 2012). Also, organisms contained in probiotics do not usually colonize the GI tract, and thus probiotics must be consumed on a regular basis to receive benefit (Maukonen & Saarela 2013). That is why I use them as a temporary measure, say after a fast, during a colon cleanse, or when (however rarely) taking antibiotics, but not as a long-term solution for balancing gut microbiota.

Prebiotics: Prebiotics are non-digestible food components (typically carbohydrates) selectively used by beneficial gut bacteria, thus potentially shifting microbial composition towards advantageous bacteria and away from pathogens (Bäckhed et al. 2012). The pill form ensures passage all the way to the small and large intestine where its targets await their meal. Some dietary plant fibers also gain access to the colon, as the small intestine does not break them down. The best sources of naturally occurring prebiotics are vegetables such as artichokes, onions, chicory, garlic, and leeks.

Prebiotics have been successfully applied in the modulation of low grade inflammation in obesity (Doré & Blottière 2015). As with probiotics, they require consistent supplementation to receive benefit.

Conclusion

The three most important aspects for a healthy gut are a plant based, whole foods diet, regular exercise, and drinking enough water. Adding the occasional fast or cleanse into the mix should support your detox capacities and keep your GI tract happy and functional.

Evacuating your bowels when your body requests it is one of the simplest, effective and most important ways to keep a healthy gut and body. Feel the urge? GO! If you’re holding back all the time, you may pay with constipation and fecal compaction, potentially delaying stool transit time. This may produce knock-on effects such as putrefying proteins, fermented sugars, and rancid fats – nutrients turned toxins – in your gut. Not a desired and easily avoidable outcome.

To me, simple is best. Consuming the right foods automatically takes care of a lot and resets gut microbiota in the process. By choosing what we eat and drink, we decide directly which bacteria we feed and what nourishment we offer our own cells, too. Tea phenolics (e.g. epicatechin in green tea), for example, significantly repressed disadvantageous bacteria, while affecting beneficial strains to a much lesser degree (Maukonen & Saarela 2013). Adapting our diet by including foods that serve us and dropping those which do not seems an excellent strategy. To arrive at the diet that’s right for you, it likely takes trial and error. No worries.

Adapting dietary habits seems the best tool to achieve a naturally healthy gut – and thus overall wellbeing – long-term.

For more articles like this, sign up to Holistic Health Global’s monthly Healthy Living Newsletter or like HHG on Facebook! You can also connect on YouTube or visit: HolisticHealthGlobal.co.nz

References:

Unless cited otherwise, this article drew on information from Giulia Enders’ book, listed below.

Books

- Group, E. 2010. Green Body Cleanse

- Enders, G. 2015. Gut: The inside story of our body’s most underrated organ (English)

- Enders, G. 2015. Darm mit Charme: Alles über ein unterschätztes Organ (German)

Papers

- Bäckhed et al. 2012. Defining a Healthy Human Gut Microbiome: Current Concepts, Future Directions, and Clinical Applications. Cell Host & Microbe 12, November 15, 2012.

- David et al. 2013. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome.

- Derrien M and JET van Hylkama Vlieg. 2015. Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends in Microbiology 2015 (23/6): 354-366.

- Doré J and H Blottière. 2015. The influence of diet on the gut microbiota and its consequences for health. Cur Op Biotech 2015 (32) 195–199.

- Foster JA and K-A McVey Neufeld. 2013. Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression.

- Luna RA and JA Foster. 2015. Gut brain axis: diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Cur Op Biotech 2015 (32) 35-41.

- Maukonen J and M Saarela. 2013. Human gut microbiota: does diet matter?

- Sommer F and F Bäckhed. 2013. The gut microbiota — masters of host development and physiology.

- Vogt et al. 2015. Chemical communication in the gut: Effects of microbiota-generated metabolites on gastrointestinal bacterial pathogens.

- Xu J and JI Gordon. 2003. Honor thy symbionts.

Websites

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA). 2014. Obesity is common, serious and costly.

- Chakrapani Ayurveda

- Colonic Health Centre

- Global Healing Center (Dr. Edward Group)

About the author:

Katrin Geist loves exploring the mysteries of life. Initially doing so as a biologist, she now devotes her time to helping people regain and maintain their wellbeing through Reconnective Healing and wellbeing coaching. Biophysics taught her the importance and far reaching implications of a truly holistic approach to wellbeing, and to life at large. More and more, she begins to understand how energy, frequency, and information shape our lives – knowingly or not.

Katrin Geist loves exploring the mysteries of life. Initially doing so as a biologist, she now devotes her time to helping people regain and maintain their wellbeing through Reconnective Healing and wellbeing coaching. Biophysics taught her the importance and far reaching implications of a truly holistic approach to wellbeing, and to life at large. More and more, she begins to understand how energy, frequency, and information shape our lives – knowingly or not.

Katrin holds a BA from the University of Montana, U.S.A. and an MSc in biology from Berlin University (FU). This science background enables her to communicate scientific subjects in an accessible way, so that everyone can benefit from information otherwise often confined to technical experts.

Katrin has held international wellbeing clinics in several countries and currently works from her New Zealand office in Dunedin. She feel privileged to serve in this capacity and invites you to experience something different. Take back the reins of your health and discover more!

To contact Katrin for personal or remote sessions and to invite her for a seminar or presentation, please call or email her. You can contact Katrin via Facebook • Email • Website • or telephone 0064 (0)21 026 95 806 (NZ mobile).

For more articles like this, sign up to Holistic Health Global’s monthly Healthy Living Newsletter or like HHG on Facebook! You can also connect on YouTube and online at HolisticHealthGlobal.co.nz

Recommended articles by Katrin Geist:

- The Amazing Health Benefits of Beetroot

- Striking the Balance: Why Optimal Body pH Matters and How to Achieve It

- The FAT Facts: Butter vs Margarine

- 10 Significant Reasons Why Regularly Drinking Green Tea Is An Awesome Healthy Living Habit!

- Truly Healing From Cancer and Preventing It Altogether

- Research Shows Promising Effects Treating Advanced Cancer with Light Frequencies

- Depression & Anxiety: Discover 3 Powerful, Drug-Free Ways that Help Thousands, Naturally

- Navigating the Plastic Jungle – Understanding What’s What PLUS Easy Ways to Adjust Your Plastic Use

- Canned – Do Energy Drinks Truly Give Us Wings Or Is It All Real Bull?

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”110027″]